Example: You have d major scale but you make a c flat accidental, does it just naturalize c back to its basic form or make it an enharmonic b? Ive tried searching on google but found nothing. It's like flats and sharps raise and lower notes by a 1/2 step so technically c-flat in the d major scale should be c-natural right? Or do accidentals take the most basic form of the note and then alter it?

-

2It's common to see a natural sign and a flat sign side by side, where the intention is to play a flat note in a key where the note would otherwise be sharp (like C-flat in D major). – Dawood ibn Kareem Nov 07 '19 at 06:11

-

1Careful, they might delete your question. ;) (Think about it) – Andrew Nov 08 '19 at 20:19

5 Answers

The answers so far seem to have missed the point. I think you're asking in a key where there is C♯ in the key sig., and you come across a C note with a flat sign just before it, what do you play.

You'd play a C♭ note - equivalent on most instruments to sounding like a B. Reason being, any accidental changes a base note into sharp or flat, and a natural sign means it gets played as a standard note - one of the white keys on the piano, if you like. A double sharp or double flat changes the note it's before into a note a tone higher or lower, respectively.

Put another way, the key sig. changes particular notes whereas an accidental treats the note as a natural that needs changing in the shown way.

Having said all that, I cannot think of a single reason why a C♭ note would need to be written in key D..!

- 192,860

- 17

- 187

- 471

-

1oh thank you, your answer was well written and detailed to the point where i understand exactly what you mean. – Tanaka Tanaka Nov 06 '19 at 15:55

-

10

-

2@ggcg - I hoped someone would work one out! Thanks, now I can think of a single reason..! – Tim Nov 06 '19 at 16:43

-

-

@ggcg - I have met many similar circumstances where the writer would have used B instead... Standards keep dropping! – Tim Nov 06 '19 at 17:36

-

1I hear you. I personally fell like sight reading is easier when the notation follows traditional convention. But then again, that's how I was raised. – Nov 06 '19 at 21:30

-

Mel Bay does s good job teaching sight reading of chords and provide pieces in keys with a lot of sharps or flats, it gets interesting. – Nov 06 '19 at 21:31

-

@Tim One likely occurrence of a Ddim7 chord in the key of D major would be as a delayed resolution after the five chord. Usually a B would be in the melody in this case, which makes spelling it as a Cb quite ungainly! If that bugs you, just think of it as a Bdim7 triad in first inversion. There's no standard to drop. – Max Nov 07 '19 at 02:18

-

I interpret the dropped standard as the poor notation rather than the use of the chord. – Nov 07 '19 at 11:08

-

@ggcg - yes, the poor notation - although probably reading Cb is less easy than reading B. The 'dropped standards' was said in jocular fashion. We're very short on humour on this site. Musos can't afford to be too serious, surely? – Tim Nov 07 '19 at 11:22

-

1I personally find it easier to read chords when written correctly as the shape made by the stacking of notes immediately tells me what hand shape to use. Changing the cb to a b messes that up for me. – Nov 07 '19 at 11:37

-

@ggcg - as a chord written on a stave, certainly, although this question was originally about single notes. We've strayed somewhat! – Tim Nov 07 '19 at 12:03

-

For older notation, before the invention of the natural sign, this answer is incorrect. Guest's answer is therefore more complete. – phoog Nov 08 '19 at 17:11

-

@phoog - thanks for pointing that out. There is no mention in OP's question of older notation, and the natural sign has very little relevance to the question either. Don't believe that makes this answer incorrect. – Tim Nov 08 '19 at 17:18

-

@Tim perhaps "incomplete" is a better word. The point is that there certainly are instances in which the flat sign would be used to indicate an F natural or C natural, in contrast to what this answer says. The natural sign is relevant because those instances will mostly be found in music that was written before the invention of the natural sign (because there was no other way to cancel a sharp sign at the time except by using a flat sign). Unfortunately I do not have time to look for examples right now, but I may do so if I can find some time over the weekend. – phoog Nov 08 '19 at 22:00

If you are reading a modern edition of the music, a C with a flat in front of it always means C flat, which is the same pitch as B natural.

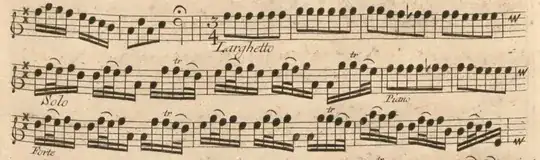

However in music scores written in the 18th century this is not always the case. For example in the attached violin part (by Vivaldi) published in 1711, it is obvious from the context (as well as from reading contemporary books on music theory and notation!) that the "F flat" really means F natural.

Later on in the same piece there are also some "C flats" that are clearly C naturals.

Note that the rules for how long an accidental stayed force were also different at that time. For example the two F's in the following bar would also be F naturals.

This notation was still in use beyond the death of J S Bach - and was been responsible for a few mistakes in interpretation that survived for 100 or 150 years, when old manuscripts were discovered and republished by people who didn't know about the old notation system.

- 121

- 3

-

1Interesting. Those 'flat' signs look suspiciously like unfinished natural signs to me! Love the 'double sharp' signs in the key sig. That would make interesting sounds. – Tim Nov 07 '19 at 08:06

-

-

@yo' I'm not particularly well familiar with this period of music notation, but there are certainly earlier (15C, 16C) examples where flats and sharps were used to cancel each other. This makes sense knowing that they derive from the round and square b that represent the notes a major third above G and a fourth above F, respectively. These were "fa" and "mi" respectively in Guido's system, and as the system was extended with "false" hexachords, the signs applied to other notes to show that they should be "fa" or "mi" in a false hexachord. The natural also came from the square b, only later. – phoog Nov 08 '19 at 17:25

I assume standard convention here as opposed to repeating any accidental to each note, where it applies.

A natural sign neutralizes a previous accidental (whether part of key signature or individual), so c# naturalized returns to c, b flat naturalized returns to b.

A repeated sharp to an already sharped note does not accumulate, you still have a simple sharp. (Same for flat). In clean notation there is no alternative to naturalizing before applying the other accidental.

Should you desire a double sharp/flat, this has be indicated by a double sharp/flat symbol. Most probably a simple sharp/flat to the same note came before.

A natural sign is also sufficient after a double sharp/flat to arrive back at the base note.

- 11,034

- 1

- 25

- 56

maybe you mean c natural? it is called c natural not sharp or flat. if you play c natural in D major scale then you have played accidental. that's it.

- 625

- 5

- 16

-

3Since to the key signature of D major consists of two sharps, we deal with C sharp, not C natural here. OP is asking, what happens to this C sharp if one adds a flat. – Arsak Nov 06 '19 at 15:11

C♭ is always B♮ (in equal temperament)

- 874

- 5

- 12

-

3

-

OP is asking if C♭ can mean something different based on the key signature so yes it does – Legorhin Nov 06 '19 at 15:40

-

2@Legorhin It might help to understand your point, if you added a sentence or two of further explanation. – Arsak Nov 06 '19 at 16:11

-

@Arsak at this point the accepted answer is better than my point so I won't bother – Legorhin Nov 06 '19 at 16:24

-