In almost all music theory websites and books I have read it defines a passing 6/4 chord as a chord that passes between the same root and 1st inversion triads (eg I to I6) but I have not seen much that says that passing 6/4 chords can also be used between two different root position chords. Is there a reason why music theory teachers normally teach this way? Do 6/4 chords not work when moving between two different chords?

3 Answers

Can this happen? Sure. Is it common? No.

(For this answer, I'm going to assume you're interested in standard "theory" answers that are grounded in stuff like textbooks that do four-part harmony in a sort of 18th-century style. If you're writing rock or pop music or something, all bets are off. Do what you want.)

Let's start with what a 6/4 chord is in the first place. The way we tend to be taught about "chords" or think about "chords" in general seems to assume that a chord is a somewhat stable sonority. It may have tendencies to resolve (like seventh chords), but we think of it as a coherent "thing." Whereas so-called "non-harmonic tones" are not part of "chords." Those aren't part of "things" -- that are ancillary bits of music, or at least that's what textbooks imply.

Here's the problem with 6/4 "chords." In actual 18th-century style as practiced by 18th-century composers, 6/4 "chords" were more like collections of non-harmonic tones as we'd conceive of them today, rather than stable sonorities. (This is what ttw's answer gets at in the notion of "more of a coincidence of voices than a vertical object.") The fourth above the bass made a 6/4 chord a "dissonance" according to 18th-century rules. It needed to be resolved. Moreover, dissonances in that style tend to be approached and left by step. Not leapt to. Not leapt from. So that fourth above the bass would not only need resolution, but it needs to be moved into and away from smoothly, either by holding the note or going by step.

None of these constraints apply to a 5/3 ("root position") major or minor triad, nor to a 6/3 ("first inversion") chord. The 6/4 is different. In other words, it wasn't a (consonant) "thing" in the same way a 5/3 or 6/3 was usually a "thing." (Yet Rameau made the 6/4 into a "thing" when he came up with his detailed theory of inversions, but that took quite a while to catch on.)

You may already have a sense of some what I've said, but it's important to realize why the 6/4 chord is an unusual sonority in 18th-century style except in certain idiomatic places, like cadences, hence the cadential 6/4 chord. Or sometimes as a confluence of neighbor tones, which is what the "pedal 6/4" almost always is -- a 5/3 chord that just happens to have two neighbor tones that move up and back down, creating 5-6-5 and 3-4-3 lines concurrently. (One of those chords can also be a seventh chord, e.g., making a 5-6-7 line, so in that case the "6/4 chord" is really a neighbor tone and a passing tone.)

But rather than just calling these "neighbor tones," when they are held for a few beat or two (or even an entire measure), we begin to think of this vertical collection of notes as a "thing" that should have a label. So we slap a "6/4 chord" label on it.

The so-called "passing 6/4" is a rare thing in 18th-century style. If you look at Bach chorales, where bass lines do something like move 1-2-3, connecting a root position and first inversion chord, Bach inevitably prefers either viio6 or V4/3 to a 6/4 chord. The same applies to most other 18th-century styles by most composers.

Passing 6/4 chords aren't common. They're not unheard of. But they're a less common choice. And when they do occur, they mostly occur in specific paradigms, specifically usually involving a so-called voice-exchange where the bass moves either 1-2-3 or 3-2-1 and some upper voice moves the opposite (3-2-1 or 1-2-3) against it. The fifth of the first chord is held as a common tone, and the other note usually flirts with the leading tone (as usually the progression implies a local I-V-I function) and goes back. Just like the pedal 6/4 almost always has certain voice-leading for all the voices, same with the much less common passing 6/4. The "pedal 6/4" would have been viewed by most composers in the 18th-century as a set of passing tones that moved this way and neighbor tones that moved that way, etc., according to prescribed formulas.

The passing 6/4 is such a secondary and less common choice in 18th-century style that I personally wish theory textbooks would delay introducing it until students have practiced using the more common options (viio6 or V4/3) first. But still, most textbooks include it as it does happen.

Now, what you're asking about is an even rarer option -- using a stepwise bassline outside of that idiomatic 18th-century paradigm I just described. Does it happen? Sure. Is it an option a beginning student should attempt without a good sense of 18th-century style? Probably not.

Part of that issue is the harmonic emphasis in music theory pedagogy today, compared to a much more melodic/line-based sense of instruction historically used for 18th-century music. If you understand how lines are naturally supposed to flow and what the idiomatic motions are, you might occasionally have a confluence of a 6/4 chord passing when connecting chords with different "roots." Sure. It can happen.

But to answer the question, "Is there a reason why music theory teachers normally teach this way?" It's because they're not really teaching you about a chord, per se, which you can use anywhere. Most textbooks are teaching you a specific paradigm or idiom, which is connected to the harmony around it, the voice-leading, etc., even if that's not always made clear. The passing 6/4 that connects root position and first inversion chords is the most common use of this uncommon sonority to begin with.

And in my experience, students want to make use of 6/4 "chords" everywhere if the textbook gives them some tiny latitude, because most textbooks (and most teachers) don't explain what I did in the first few paragraphs here about how 6/4 chords simply aren't stable chords in 18th-century style, no matter how "normal" they sound to modern ears. They only tend to occur in places where voice-leading lines up in certain idiomatic ways -- and until you understand the reasons why the voice-leading occurs that way and where it can occur elsewhere, chances are by putting a passing 6/4 somewhere else, you're not going to handle it in an idiomatic 18th-century fashion.

My suggestion, if you really want to imitate 18th-century style, is to go and analyze a bunch of actual 18th-century music until you find a few 6/4 chords that do what you want. Then you'll have a basis to imitate. (If you actually do this, you'll probably quickly discover how rare the passing 6/4 really is.) Until then, if the goal is to imitate 18th-century style, better to follow the textbook models. If the goal is to imitate 19th-century style, I'd have a similar recommendation, though you'll begin to see increasingly free use of 6/4 chords in other situations over the course of that century.

And once again, if the goal isn't to imitate 18th-century style, but just to harmonize stuff, just follow your ear. Do what "sounds good" to you.

- 12,592

- 23

- 50

-

I think I've just found an example of passing 6/4 in Mozart Piano Sonata in B flat major, K.333, third movement. Bar 132, the chords (in modern notation) are Bb7/D-Fm/C-G7/B. The Fm/C seems to be a passing 6/4 here, no? – Divide1918 Aug 07 '21 at 03:52

-

@Divide1918 - Sure, you could classify that as a passing 6/4. It doesn't satisfy OP's two root position chords, but it's definitely different from the most common paradigm for passing 6/4's. But again, to me the label "passing 6/4" doesn't actually tell us much about how this sonority works. What's actually going on is the Ab is the 7th of the first chord, it's held as the bass changes, but resolves down (as expected) on the downbeat of the next bar.The F is held through the bass PT note, becomes a 7th in the next bar, and then resolves down in the following bar in a different voice. – Athanasius Aug 07 '21 at 18:55

The passing 6/4 chord is probably best understood as voice leading motion.

Start with understanding that "strong" progressions of roots by fifth/fourths involve two voices moving, one held.

The non-passing resolution is the cadential or pedal type...

...categorically that's an appoggiatura type resolution. It ends on a root position chord, so that's half of what we're looking for, but it isn't passing motion.

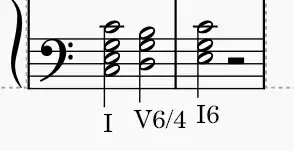

But if we move two voices up from a 6/4 chord we get the familiar passing motion between tonic chords...

You could force it move to a root position chord, we will get the C D E "passing" motion, but it will be a "weak" progression to iii with only one voice moving...

You can also do it chromatically, but in that case a 6/3 or 6/5 chord seems the common way...

...the passing motion is C C# D. The passing chord can also be a dim7 chord.

If you make the passing chord a 6/4 or 4/3 chord it would be...

...and that seems fine, but the passing motion is now not in the bass, but in an upper voice.

I don't think I've seen in stated in textbooks, but the "passing" part of a passing 6/4 seems to be associated with the bass voice.

- 56,724

- 2

- 49

- 154

I haven't seen anything in a theory book so I tried it on the piano using a 64 passing chord. I6-V64-vi6 seems to work; I6-vii6-vi6 may be smoother. The "passing" chord seems more of a coincidence of voices than a vertical object; anything with good voice leading usually works fine. (In 4 voices, I6-V43-i6 works too.)

- 25,431

- 1

- 34

- 79