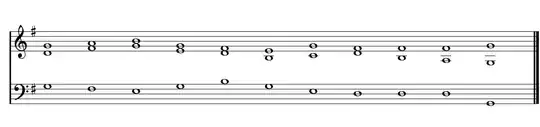

I am learning 3 part counterpoint and am doing an excersize where I am using the CF as the middle line and composing a melody above and below the CF. If you notice towards the end (chords 7 - 10) there is a part with oblique motion and a descending middle line. Basically parallel 10ths. Is this allowed when used like this and is it seen as good or bad writing?

-

2Do you know why parallel fifths and octaves are avoided? – piiperi Reinstate Monica Mar 09 '21 at 10:00

-

because they sound like the same note instead of two different notes and discourage vocal independence between voices? The melodies become like one note due to the perfect consonance – Mar 09 '21 at 10:02

-

Does that happen with 3rds, 6ths, 7ths, 10ths, etc.? – piiperi Reinstate Monica Mar 09 '21 at 10:04

-

Don't know. I guess it shouldn't. If you listen to what I composed, it definitely thins out towards the end as does when you use parallel 5ths or octaves but maybe not as bad, so that is why I am asking – Mar 09 '21 at 10:05

-

1I assume this is in the 16th-century style? I think some of the current answers are assuming 18th-century style. – Richard Mar 09 '21 at 13:02

-

@ Richard, I have no idea which style, should I care? – Mar 09 '21 at 15:35

-

1Yes. I took you to be writing counterpoint in the style of Fux (after Palestrina), which is the typical starting place for learning counterpoint. But styles and rules change over time. Counterpoint in the 20th century is radically different from the 16th. @Richard will know more than I do about changes between the 16th (Fux) and 18th centuries. – Aaron Mar 09 '21 at 16:02

-

2Just found this: What's the difference between sixteenth century counterpoint and eighteenth century counterpoint?. – Aaron Mar 09 '21 at 16:05

-

1@armani I'm assuming 16th because you start and end on harmonies without thirds. This is common in the 16th-century style but would be a big error in the 18th-century style. If your instructor (or text) has emphasized starting with a fifth/octave above the bass, then you're definitely in the 16th-century style. – Richard Mar 09 '21 at 16:06

2 Answers

Parallel 10ths -- that is, two voices moving together in 10ths -- are fine. Parallel 3rds and 6ths, and by extension 10ths, are even encouraged for short segments (too long -- more than about three chords in a row -- and the independence of voices is lost).

The problem here is that both voices stay on the same pitch. This is generally discouraged -- at least one of the two voices should move, and even a single voice should not repeat the same pitch more than once consecutively.

So, the move from chord 7 to chord 8 is fine. The parallel 10ths between top and bottom voices will sound quite nice. But the static top and bottom voices in chords 8, 9, and 10 are not considered good counterpoint.

(There's also a second problem: a hidden octave between the middle and bottom voices in the final two chords.)

- 87,951

- 13

- 114

- 294

-

Thanks Aaron, can you please confirm you see a parallel octave somewhere? can't see one in there – Mar 09 '21 at 15:55

-

That's why it's referred to as a "hidden octave" or "hidden parallel". The idea is that the lowest voice moves from D down to G, passing by A (a singer at the time these "rules" were being devised would fill in the pitches between D and G), creating a parallel octave with the middle voice. To the best of my memory, you can avoid the issue by moving the low voice upward (to a unison with the middle). – Aaron Mar 09 '21 at 15:59

-

This cadence was provided by my teacher as a viable cadence option for a CF as the mdidle voice. He said in 3 part writing " sometimes direct motion to a perfect consonance is unavoidable" and he said that it was a concesion that had to be made. He recommended to only use it at the cadence. Please let me know if you think he is wrong. – Mar 09 '21 at 16:22

-

In addition to Aaron's answer there are three other things you should maybe consider:

The first chord has no 3rd, only root and fifth. I like it but it would be considered wrong in Bach style counterpoint. It is so long since I have done strict counterpoint I am not going to comment on whether on not it is acceptable in that tradition.

In the second chord you have doubled the 3rd of a major chord if it is intended to be the dominant chord. If you could find a way to avoid this it would probably improve the counterpoint. The absence of the root, if the chord is the dominant, or fifth if the chord is a leading note chord, makes the harmony ambiguous. There again the voice leading to the submediant chord does help to compensate for any harmonic problem but to my ears the doubled leading note is not good. And if it is meant to be a leading note chord it should be in the first inversion.

The other point is that the ninth chord is the mediant chord between two root position dominant chords; within traditional harmony would be considered weak. The mediant chord in a major scale is not always easy to use. The B in the cantus firmus could almost be considered a passing note but as Aaron pointed out the static parts in these three chords is not the best solution.

Sorry Aaron, but you are wrong about the hidden parallel octaves in the last two chords, there is a good overview here:

Despite the suggestions you have made a good attempt at this exercise and it would work with a keyboard instrument. With unaccompanied voices though it would not be quite so successful. However you asked about parallel tenths so my reply is not what you asked but as you are studying I thought it may be useful.

- 276

- 1

- 6

-

THank you for your comments Ian. Not sure if this is Bach style but the examples the teacher I learned this from uses Aloys, Joseph and Fetis. The CF I am using is by a composer called Nadia Boulanger. With that info your guess is much better than mine. Youre right about the doubled leading tone :) I didn't remember about that when composing this. I think I am going to start over taking your and Aarons considerations into account. Oh and one last thing, I am pretty sure that an 8/5 chord on the beginning of the opening chord is quite acceptable. – Mar 09 '21 at 15:49

-

@armani Aloys and Joseph are characters from Fux's textbook on 16th century counterpoint. It was written during Bach's lifetime, somewhat as a reaction against "new" trends in composition. Nadia Boulanger was one of the most important music teachers -- particularly of composition -- of the 20th century. – Aaron Mar 09 '21 at 18:05