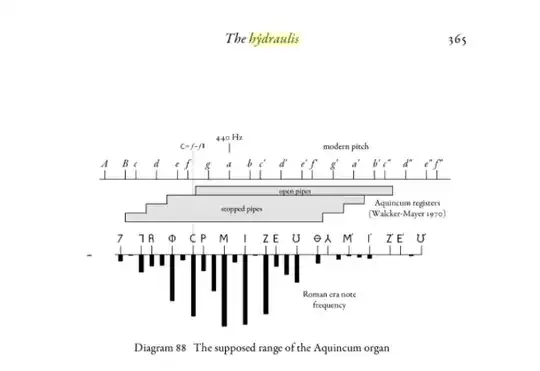

I am trying to reconstruct the tuning of the Roman water-organ (hydraulis) of Aquincum. The original instrument had 13 pipes for each of the 4 registers (three stopped pipe registers and one open pipe register), and it was possible to play one, two, three, or all four pipes corresponding to each key at the same time.

The best description I found of what could be the tuning comes from the booklet of "Apollo & Dionysus" cd (https://www.chandos.net/chanimages/Booklets/DC4188.pdf), which is based on an actual hydraulis reconstruction by Justus Willberg:

The organ is tuned to an ancient tonal system, drawing upon a range of sources, including Bellermann and Koine Hormasia (Codex Palatinus 281, et al.). The registers are assigned individual modes (Hyperlydian, Hyperiastian, Lydian and Phrygian), allowing a specific set of notes to be played in each register: proslambanómenos, hypáte hypaton, parypáte hypaton, diápemptos, hypáte, parypáte, khromatiké, diátonos, mése, parámesos, tríte, paranéte, néte. In today’s notation this corresponds approximately to the pitch series D E F G A B♭ B C' D' E' F' G' A'. The organ can also be played with all the registers switched on, which results in a characteristic timbre in which the open Hyperlydian register dominates.

What I understand with my limited musical knowledge is:

- the register of the open pipes (which should be the highest pitched one) was Hyperlydian;

- the three registers of the stopped pipes were Hyperiastian, Lydian and Phrygian;

- one of the registers (the highest one?) was tuned according to the scale (that I do not recognize) D E F G A B♭ B C' D' E' F' G' A'.

My question is: how was this organ tuned? What were the pitches for each register? It seems they could be played at the same time, but would they sound nice together?

Edit:

As suggested by user Owain Evans, this is the instrument:

However, it can't be the setup presented in Hagel's book since (1) Hagels himself doubts the correctness of Walker-Mayer reconstruction and (2) none of the registers in Hagel's picture (borrowed from Walker-Mayer, actually) has the range proposed by Willberg

from HAGEL, S. (2018). Ancient Greek music: a new technical history. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, p365.

from HAGEL, S. (2018). Ancient Greek music: a new technical history. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, p365.