You don't buy stocks and then ignore them.

Either you or your advisor needs to either keep up on trends and news, buying and selling stocks dynamically on a "best bet" basis... this is called the "Rain man stock picker" method. Or, by having a fixed investment plan in which buys and sells are done according to a plan in response to published market data, in which case no "Rain Man" is needed, just an intern to make the scheduled buys and sells. Which can be automated on a computer, really.

This means "you" will be actively walking your way out of stocks as they fall, and buying into stocks as they rise. By the time they bankrupt, you are long gone.

As you can see, this is way too much task load for you to DIY.

A basket of stocks

To the bare novice, investing seems like a game of "picking stocks". You can do it that way if you really want to. If you did, you would end up with a basket of stocks. Okay.

Well, if someone selected a basket of stocks, and then sold you shares in that basket, it would be the same as you buying those stocks individually - except you would trade it as one unit. This is a thing, called a mutual fund. This is the key to consumer investing.

You can get two kinds. Kind #1 is "Rain Man stock picker guy" aka a managed fund. This is where a smart stock picker and research staff simply research and trade stocks all day, always trying to beat the market. They are picking for you. You pay them a tribute of about 1.5% per year for their services.

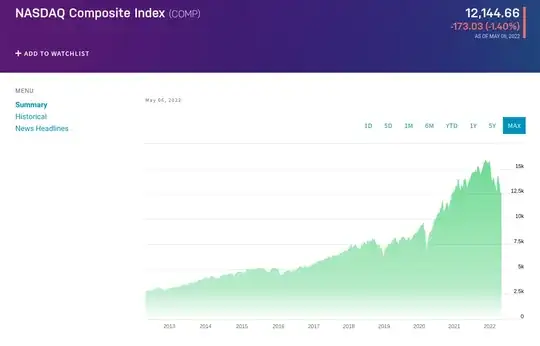

Markets have an index (basically the sum of all stocks on a list such as S&P 500) and you can use them as a gauge to determine how well your picker is picking. Can they beat the market average? You bet. Can they beat the market average by more than their 1.5% expense ratio? HAHA... interesting science on that point.

John Bogle crunched a bunch of historic data and said "they don't, except occasionally by luck, and they can't repeat it". A fund manager replied:

"LOL, too bad consumers can't just buy the index!"

And so Bogle created a mutual fund that is exactly the S&P 500 called VFINX. This is the second, formula-based basket of stocks I referred to: the index mutual fund. And because interns and scripts work for peanuts, the expense ratio is blissfully low - like 1/20, maybe 0.08%. That means you are making 1.42% more money per year, assuming your stock picker is just average.

Bogle put the research into a book, called "Common Sense on Mutual Funds", if you want the details.

A fund like VFINX (now VFIAX or VTSAX) is a "fire and forget" investment for a consumer. I'm mentioning Vanguard funds so Bogle can make a little on the good idea, but every major broker offers these. Some even charge outrageous and unnecessary sales loads!

And the fund performance speaks for itself. Just compare any index fund to a managed fund trading the same kind of stuff (e.g. large-cap managed funds to S&P 500 index funds).

Note that comparing index funds (especially index ETFs) to the market can get weird, because they fold dividends back into the fund value, so it may actually outpace the S&P.

As such, ETFs are a big help on tax day, because you don't have to report within-mutual-fund trades or dividends every year nor pay taxes on them. No income or taxation occur until you sell the ETF.

ETFs are simply mutual funds packaged and traded as a stock - VOO and VTI are the ETF versions of those funds I just named. Normal mutual funds have a special trading mechanism (they sell only at end of day, and the day after you notify to sell) whereas ETFs trade instantly when the market is open.