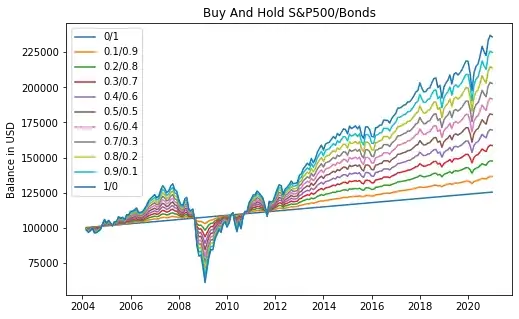

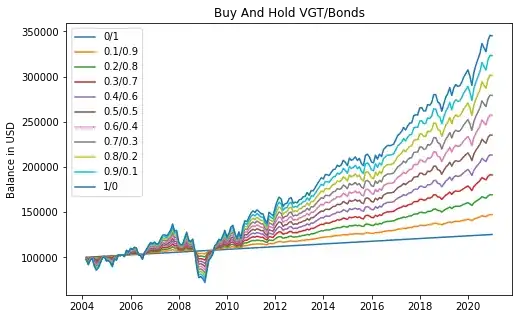

I'm 35 and I want to start investing for my retirement. My question is, why would you care about volatility if your investment horizon is 30+ years? In order to get a more clear picture of volatility risk, I gathered some data in Python and computed portfolios with varying percentages of risk-free bonds, with a buy and hold of 100k USD initial:

Looking at the graphs, the only reason I could think of is that when you need your money in times of bearish markets, you can lose 30-40% of your capital. But if you can miss the money, and won't need to withdraw it early, why would one care about volatility?

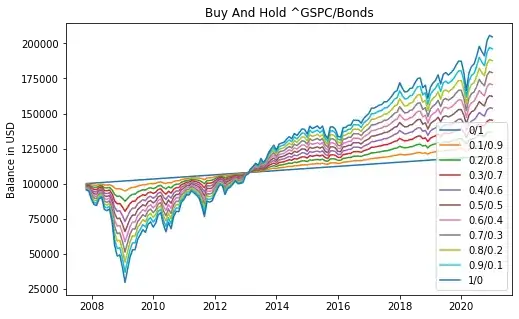

Edit Someone requested to see what would happen if you invested on the peak just before the 2008 crash.

As you can see the timing would have meant five years of a negative balance, before you broke even again.