I’m applying for a mortgage, and found a potential lender from a referral from my real estate agent. The initial application process seemed normal and very similar to what I’ve experienced with other banks. I expected to verify my assets by providing documentation such account statements, but was instead asked to link my bank accounts with them using a third party website (The domain name is finicity.com - so I’m fairly sure it’s this).

The lender set my expectations with this via email:

What we don't do:

- We don't ever see or have access to your login information.

- We don't use your information for any other reason than to process your loan.

- We don't have access to take any actions in your accounts - we access read-only information, just like the documents you'd otherwise have to send.

I have a checking account with Chase and linking the account with the lender was done by redirecting to Chase.com (where my password manager automatically filled in my username and password) and enabling some permissions. Chase sent me an email and the lender appears as a linked application. This strikes me as entirely legitimate.

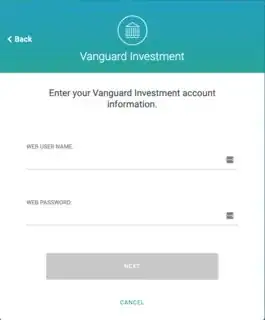

However, I have a brokerage account with Vanguard, and the service is asking for my username and password. I am VERY uncomfortable with this.

Is this a reasonable request nowadays? Or should I push back and insist on verifying my assets with account statements?