The following identity is a bit isolated in the arithmetic of natural integers $$3^3+4^3+5^3=6^3.$$ Let $K_6$ be a cube whose side has length $6$. We view it as the union of $216$ elementary unit cubes. We wish to cut it into $N$ connected components, each one being a union of elementary unit cubes, such that these components can be assembled so as to form three cubes of sizes $3,4$ and $5$. Of course, the latter are made simultaneously: a component may not be used in two cubes. There is a solution with $9$ pieces.

What is the minimal number $N$ of pieces into which to cut $K_6$ ?

About connectedness: a piece is connected if it is a union of elementary cubes whose centers are the nodes of a connected graph with arrows of unit length parallel to the coordinate axes.

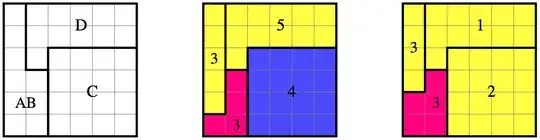

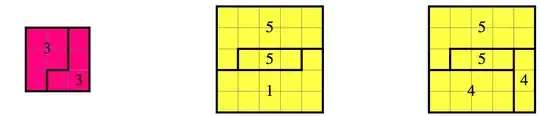

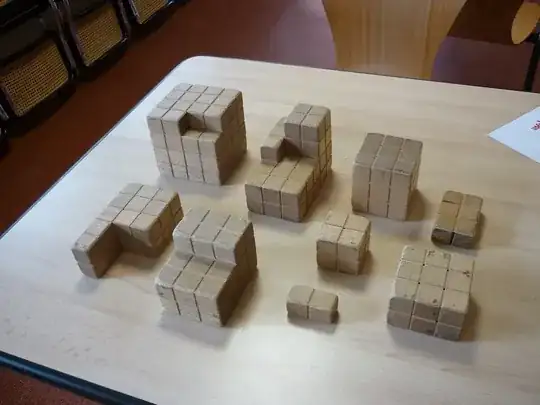

Edit. Several comments ask for a reference for the $8$-pieces puzzle, mentioned at first in the question. Actually, $8$ was a mistake, as the solution I know consists of $9$ pieces. The only one that I have is the photograph in François's answer below. Yet it is not very informative, so let me give you additional information (I manipulated the puzzle a couple weeks ago). There is a $2$-cube (middle) and a $3$-cube (right). At left, the $4$-cube is not complete, as two elementary cubes are missing at the end of an edge. Of course, one could not have both a $3$-cube and a $4$-cube in a $6$-cube. So you can imagine how the $3$-cube and the imperfect $4$-cube match (two possibilities). Other rather symmetric pieces are a $1\times1\times2$ (it fills the imperfect $4$-cube when you build the $3$-, $4$- and $5$-cubes) and a $1\times2\times3$. Two other pieces have only a planar symmetry, whereas the last one has no symmetry at all.

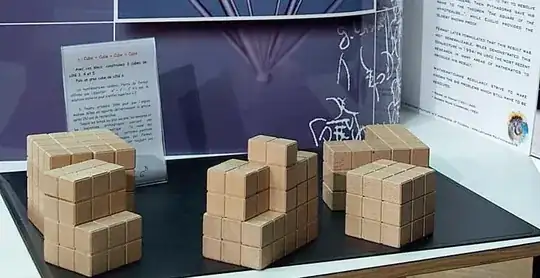

Here is a photograph of the cut mentioned above.