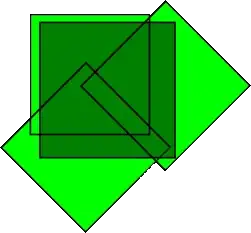

I'll expand my comment into an answer. Following Serre's suggestion in the comments, to show that $n+1$ unit cubes cover an $n$-cube of side lengths $1+\epsilon$ for some $\epsilon > 0$, it suffices to show that one may fit a unit $n-1$-cube in the interior of a unit $n$-cube. If you can do this, then you can fit a $1+\epsilon$ $n-1$-cube in the interior of a unit $n$-cube for some $\epsilon$. As Serre suggests, you may then take a vertex of the $1+\epsilon$ $n$-cube, and cover each of the $n$ $n-1$-cube faces containing it by a unit $n$-cube. Then one may use another $n$-cube to cover the antipodal vertex and the rest of the cube, possibly for a smaller $\epsilon$. This case $n=2$ is in the picture given in the question. As Bill points out in the comments, one needs an explanation as to why an $n-1$-cube fits in the interior of the $n$-cube.

To see that a unit $n-1$-cube fits in the interior of an $n$-cube, one may proceed by induction. This is true for $n=1$. Let $I=[0,1]$. By induction, suppose we have an embedding $f: I^{n-1}\to int(I^n)$. Then we have an embedding $f\times Id: I^{n-1}\times I \to int(I^n)\times I$. This gives a map which touches the boundary of $I^{n+1}$ only along $f(I^{n-1})\times \{0,1\}$. Think of this as a map $f×e:I^{n−1}\times I\hookrightarrow f(I^{n−1})\times D^2\subset f(I^{n−1})\times I\times \mathbb{R}$ ($\mathbb{R}$ is just the normal bundle to $f(I^{n-1})\times I \subset I^n\times I = I^{n+1}$). Then rotate the interval $I$ in $D^2$ by a small angle $\theta$ to get a map $e_{\theta}:I\to D^2\subset I\times \mathbb{R}$. The endpoints no longer lie on $\{0,1\}\times \mathbb{R}$. Then the map $f \times e_{\theta}: I^{n-1}\times I \to f(I^{n-1})\times D^2$ will have image in $int(I^{n+1})$ for small enough $\theta$.

http://www.uccs.edu/~faculty/asoifer/docs/untitled.pdf – Joseph O'Rourke Dec 16 '10 at 19:04

If you look at cross-sections of the unit n-cube that are perturbation cross-sections parallel to a face, the shape is determined by the slope, a linear function: the unit n-1-cube can be stretched by any linear function. You can't get a larger n-1 cube that way.

For n=3, I see how to cover one of the n-1 faces except for a neighborhood of one of its edges. With 3 cubes, you can cover 2- faces attached to S, so 4 works.

– Bill Thurston Dec 16 '10 at 21:11