Proposition. $f(n)\ge 2n+\tfrac 13\left(\sqrt{\tfrac{n}3+1}-2\right) $ for any natural $n\ge 13$.

Proof. Fix the cake cutting with the minimum number $f=f(n)$ of slices. We shall work with the graph $G$ from David E Speyer’s answer, defined as follows:

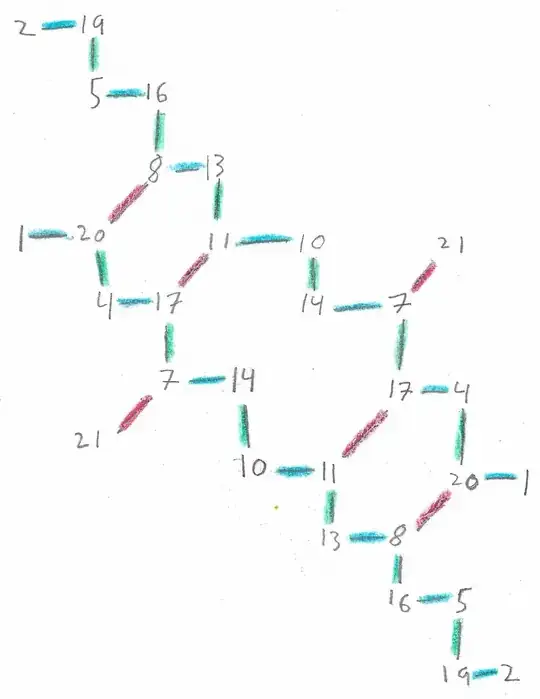

The vertices are the slices of cake. There are edges in three colors: red, green and blue. For each person who gets exactly two slices in the $n-1$ person solution, draw a red edge between the two pieces that person gets. Similarly, draw green edges for each person who gets exactly two slices in the $n$ person solution, and draw exactly blue edges for each person who gets two slices in the $n+1$ person solution.

Let $V_r$ be the set of slices given to persons obtaining at the number of slices distinct from two in the $n-1$ person solution, similarly define $V_g$ and $V_b$. Moreover, let $V’$ be the set of slices of size $\tfrac 1{n+1}$. Clearly, $V’\subset V_b$. David E Speyer at the beginning of his answer showed that $f\ge 2n+|V_g|/3$ and $f\ge 2n-2+|V_r|/3$. Similarly we can show that $f\ge 2n+2+(|V_b|-4|V’|)/3$. Put $F=3f-6n$. Then $|V_g|\le F$, $|V_r|\le F+6$, and $|V_b|-4|V’|\le F-6$.

Let $c$ and $d$ be any two distinct colors among $r$ (red), $g$ (green), and $b$ (blue). Let a $cd$-path be a path whose edges have either the color $c$ or the color $d$. Note that a single vertex is a $cd$-path too. It is easy to check that there are no closed $cd$-paths. We shall call a $cd$-path short, if its length is less than $n-2$, and long, otherwise.

It is easy to check the following lemma.

Lemma 1. Let $c$ and $d$ be any two distinct colors among red, green, and blue. Then each vertex of $G$ belongs to a unique maximal $cd$-path. The end vertices of any maximal $cd$-path $C$ belong to $V_c\cup V_d$. Moreover, if a maximal $cd$-path consists of only one vertex, then it belongs to $V_c\cap V_d$. Therefore $|V_c|+|V_d|\ge 2N_{cd}$, where $N_{cd}$ is the number of maximal $cd$-paths. $\square$

Given a slice $v$, let $|v|$ be its size. The simple straightforward calculations provide the following lemma.

Lemma 2.. Let $c$ and $d$ be any two distinct colors among red, green, and blue. Let $P$ be any $cd$-path beginning from a vertex $v$ along the edge of color $c$. Let $u$ be any vertex of $P$ and $p$ be the distance from $u$ to $v$. Then $|u|=|v|+(k_d-k_c)p/2$, if $p$ is even, and $|u|=k_c-|v|+(k_c-k_d)(p-1)/2$, if $p$ is odd, where $k_r=\tfrac 1{n-1}$, $k_g=\tfrac 1{n}$, and $k_b=\tfrac 1{n+1}$. If $|u|=|v|=\tfrac 1{n+1}$ then $d$ is blue, and, moroever, if $c$ is green then $p=2n-1$ and if $c$ is red then $n$ is odd and $p=n-2$. Note that in both cases the path $P$ is long, so if $P$ is short then it contains at most one vertex from $V’$. $\square$

Lemma 3. Let $c$, $d$, and $e$ be the colors red, green, and blue in some order, $v$ and $u$ be distinct vertices of $G$ such that there exist a $cd$-path $P$ from $v$ to $u$ and a $ce$-path $Q$ from $u$ to $v$. Let $p$ and $q$ be the length of the path $P$ and $Q$,

respectively, and $p+q$ is even. Then the path $P$ is long.

Proof. Let $C$ be the cycle which first follows $P$ and next follows $Q$. Let $e_1$, $e_2$, .., $e_{p+q}$ be the edges of $C$ enumerated along the cycle. We refer to the answer by David E Speyer again.

Let $r$ be the difference between the number of red edges among $\{ e_1, e_3, e_5, \dots \}$ and the number of red edges among $\{ e_2, e_4, e_6, \dots \}$, and define $g$ and $b$ similarly. Then we have $r+g+b=0$ ... and $r/(n-1) + g/n + b/(n+1) = 0$. .... Put $\gamma = GCD(n-1, 2)$. The integer solutions to $r+g+b=\tfrac{r}{n-1} + \tfrac{g}{n} + \tfrac{b}{n+1} = 0$ are the integer multiples of $\tfrac{1}{\gamma} (n-1, -2n, n+1)$.

Recall that each cycle in $G$ has edges of all three colors. Let $R$ be the shortest path among $P$ and $Q$. Then there exists a color among $d$ and $e$ such that $C$ has $x>0$ edges of this color and all these edges belong to $R$. When we follow $R$, the colors of its edges alternate, so David E Speyer’s arguments imply that $x\ge \tfrac{n-1}{\gamma}\ge \tfrac{n-1}{2}$. Thus the length of $R$ is at least $n-2$, and so the length of $P$ is at least $n-2$ too. $\square$

Lemma 4. Let $c$, $d$, and $e$ be the colors red, green, and blue in some order, $P$ be a short $cd$-path and $Q$ be a $ce$-path. Then $P$ and $Q$ have at most two common vertices.

Proof. Suppose for a contradiction that $P$ and $Q$ have three common vertices $v_1$, $v_2$, and $v_3$. Renaming these vertices, if needed, we can suppose that $v_2$ is between $v_1$ and $v_3$ along the path $P$. Let $P_{12}$ be the path from $v_1$ to $v_2$ along $P$, $P_{23}$ be the path from $v_2$ to $v_3$ along $Q$, $Q_{21}$ be the path from $v_2$ to $v_1$ along $Q$, and $Q_{32}$ be the path from $v_3$ to $v_2$ along $Q$, $p_{12}$, $p_{23}$, $q_{21}$, and $q_{32}$ be the length of the path $P_{12}$, $P_{23}$, $Q_{21}$, and $Q_{32}$, respectively. By Lemma 3, both $p_{12}+q_{21}$ and $p_{23}+q_{32}$ are odd. Let $P_{13}$ be the path from $v_1$ to $v_3$ which first follows $P_{12}$ and next follows $P_{23}$ and $Q_{31}$ be the path from $v_3$ to $v_1$ which first follows $Q_{32}$ and next follows $Q_{12}$. Then the path $P_{13}$ is a subpath of the path $P$ and so it is short, but the sum $p_{12}+ p_{23}+q_{21}+q_{32}$ of the lengths of $P_{13}$ and $Q_{31}$ is even, that contradicts Lemma 3. $\square$

By Lemma 2, each $rg$-path contains at most one vertex from $|V’|$, so $N_{rg}\ge |V’|$. By Lemma 1, $|V_r|+|V_g|\ge 2N_{rg}\ge 2|V’|$. But $|V_g|\le F$, $|V_r|\le F+6$, and $|V_b|-4|V’|\le F-6$. Since $|V_r|+|V_g|\ge 2|V’|$, we have $|V_b|\le 2(|V_r|+|V_g|)+F-6\le 5F+6$.

Suppose first that there exist two distinct colors $c$ and $d$ among $r$, $g$, and $b$, and a $cd$-path $P$ of length $n-3$. Let $e$ be the color among $r$, $g$, and $b$ distinct from $c$ and $d$. By Lemma 4, no $ce$-path has three common vertices with $P$, so there are at least $\tfrac{n-2}2$ maximal $ce$-paths. By Lemma 1, $|V_c|+|V_e|\ge n-2$. Similarly we can show that $|V_d|+|V_e|\ge n-2$. Then $F+F+6+2(5F+6)\ge |V_c|+|V_d|+2|V_e|\ge 2n-4$, so $F\ge \tfrac{n-11}6>\sqrt{\tfrac{n}3+1}-2$ because $n\ge 13$.

Suppose now that all $cd$-paths are short for any two distinct colors $c$ and $d$ among red, green, and blue. Fix $c$ and $d$ and let $e$ be the remaining color. Let $L_{cd}$ be the length the longest $cd$-path. By the pigeonhole principle, $L_{cd}+1\ge f/N_{cd}$. By Lemma 4, $N_{ce}\ge (L_{cd}+1)/2$, so $2N_{cd}N_{ce}\ge f$. By Lemma 1, $|V_c|+|V_d|\ge 2N_{cd}$ and $|V_c|+|V_e|\ge 2N_{ce}$. Thus $(|V_c|+|V_d|)(|V_c|+|V_e|) \ge 2f$. Since $(|V_g|+|V_r|)(|V_g|+|V_b|) \ge 2f$, we obtain that $(2F+6)(6F+6) \ge 2f=2F/3+4n$. The last inequality implies $F>\sqrt{\tfrac{n}3+1}-2$, and so $f>2n+\tfrac 13\left(\sqrt{\tfrac{n}3+1}-2\right)$.

$\square$