Essential elements$^*$ of the reconstruction algorithm were developed at MIT under the name CHIRP = Continuous High-resolution Image Reconstruction using Patch priors, as described in Computational Imaging for VLBI Image Reconstruction (2015).

The difficulty of VLBI (Very Long Baseline Interferometry Image) reconstruction is that the inversion problem is highly-ill posed, there are many images that explain the data. The challenge is to find an explanation that respects our prior assumptions about the “visual” universe while still satisfying the observed data. Bayesian approaches are generally employed for that purpose, in CHIRP machine learning is used to automatically identify visual patterns --- obviating the need for hand training of the algorithm.

A key technical innovation is a way to correct for the delays in the signal received from the various telescopes. The delays are difficult to predict, since they depend the local variations in the speed of the radio waves through the noisy atmosphere. CHIRP adopts an algebraic solution known as phase closure to this problem: If the measurements from three telescopes are multiplied, the extra delays caused by atmospheric noise cancel each other out.

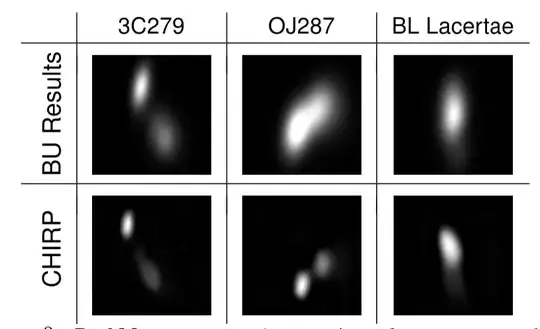

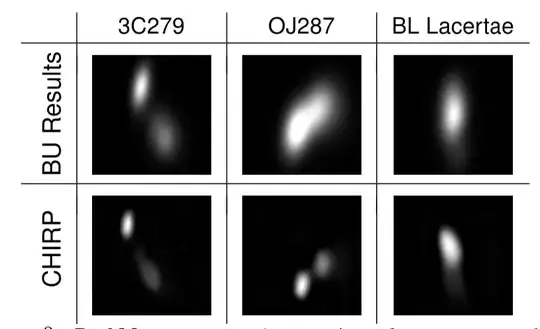

One test case that shows the resolving power of CHIRP, compared to a competing algorithm (BU) is shown below (taken from the MIT paper). Notice how CHIRP is able to resolve 2 separate, previously unresolved, bright emissions in the blazar OJ287.

$^*$ UPDATE: This statement must be qualified, as stated by the lead author, Katie Bouman: “No one person or algorithm made the image. It was actually made by combining the images produced by 3 separate imaging pipelines, leading to a more powerful result than we could ever achieve with any single method.”