For $k \ge 1$, let $f_d(k)$ be the largest possible number of points $p_i$ in $\mathbb{R}^d$ that determine at most $k$ distinct (Euclidean) distances, $\|p_i-p_j\|$.

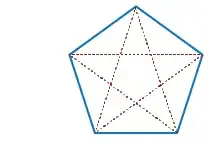

Example. For points in the plane $\mathbb{R}^2$, $f_2(1)=3$ via an equilateral triangle, and $f_2(2)=5$ via the regular pentagon.

It is clear that $f_d(k)$ is finite: it is not possible to "pack" an infinite number of points into $\mathbb{R}^d$ while only determining a finite number of point-to-point distances.

Q. What is the growth rate of a reasonable upper bound for $f_d(k)$?

I am particularly interested in $\mathbb{R}^3$. $f_3(1)=4$ via the regular simplex. I am not even certain what is $f_3(2)$. Does anyone know? Certainly $f_3(2) \ge 6$ just by placing one point immediately above the centroid of the pentagon.

But regardless of exact values, I would be interested in an upper bound for $f_3(k)$. As well as pointers to results in the literature. This question has an Erdős-like flavor, and undoubtedly has been considered previously. Thanks!