The story about Heisenberg inventing matrices and matrix multiplication in 1925 is very well known and well documented. A few weeks later, Born and Jordan read this work and recognized matrix multiplication, because one of them happened to take a course in "hypercomplex numbers" in his youth. This is how modern quantum mechanics was born.

This story clearly shows that in the second decade of the 20th century matrix multiplication was not something that every undergraduate was familiar with.

My questions:

- When did this change? (Nowadays, I would say that this is the MOST standard part of the undergraduate curriculum in the US. More standard than Calculus. EVERY science or math major is taught to multiply matrices in her first year. It was similar in the Soviet Union, and I suppose this is the case everywhere). When did this dramatic change occur? When did linear algebra become a mandatory undergraduate subject?

But an even more interesting question is

- WHY?

My conjecture is that this has something to do with the invention of Quantum mechanics. I have some arguments explaining this. But to test my arguments, I would like to know the answer to the first question, and other opinions on the second one.

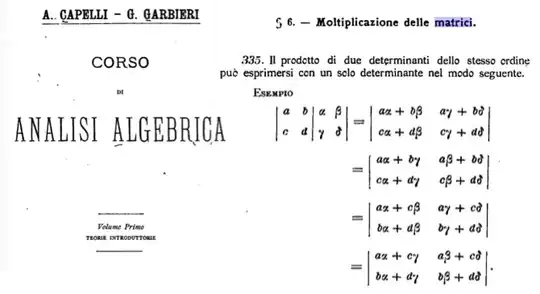

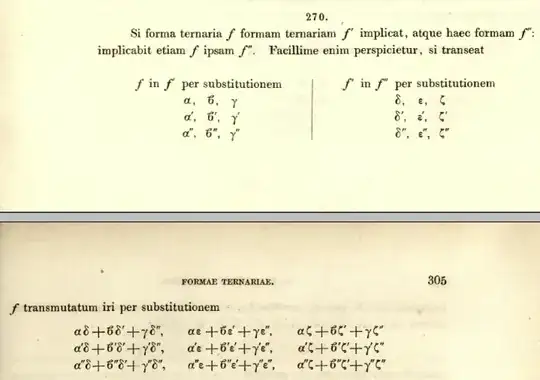

I know that matrix multiplication was introduced by Cayley (correct me if I am wrong), and that Hilbert-Courant was published in 1924. What physicists were using before Hilbert-Courant is not completely clear, but probably Thomson and Tait, or something similar. Of course, there is no mention of matrices in Thomson and Tait:-)

I understand that this may not be within the scope of this forum. Feel free to close. But I am asking in hope that someone by chance knows the answer to question 1, and will answer before the question is closed.

EDIT. Using Mathscinet, Zentralblatt and Jahrbuch, with "linear algebra", "lineare Algebra" etc. in the title, and year $< 1950$, I found a Turkish textbook of Pasha and Tefvik (1893), a textbook by H. Bohr and J. Mollerup (1938) and Russian text by Malcev (1949), from which I studied as an undergraduate. After 1950 there are many, which suggests that this curriculum revolution probably started in the early 1950s.

EDIT2: Google Ngram shows a sharp growth of the usage of the word "matrix", which begins in the middle 1940s. Against my expectation, it shows a peak in 1990 and then starts declining.

A similar question is posted on HSM