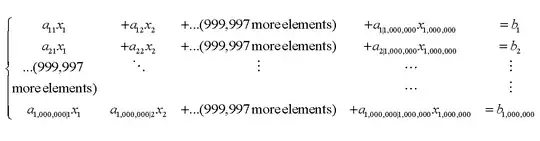

Even without explicitly introducing the language of "linear maps", "vectors", and so on, you can still develop matrices as a shorthand for such maps, thought of as exchange rates.

Example:

Machine A can make 3 sprogs and 2 sprakets a day. Machine B can make 1 sprog and 3 sprakets a day. We summarize this data in a table of values:

$$\begin{bmatrix} 3 & 1 \\ 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}$$

Where the first column represents machine A and the second column machine B, the first row sprogs, and the second row sprakets.

Now If my company buys $7$ machine As and $3$ machine Bs, what is my production capacity? This is a reasonable question for a 3rd grader, probably. All the matrix does is provide a structure for solving such a problem systematically, as:

$$\begin{bmatrix} 3 & 1 \\ 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 7 \\ 3 \end{bmatrix}$$

Multiplying a matrix by a vector should be defined to make the interpretation above valid.

Now say each sprog sells for $5$ and each spraket sells for $4$ dollars. Then we can get a new table telling us how much money machine A makes and how much money machine B makes. Again, this is a "third grade" problem, and we just introduce new notation for the problem:

$$\begin{bmatrix} 5 & 4\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 3 & 1 \\ 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}$$

Another example might be that each sprog lets another company build 2 cars and 3 buses, while a spraket lets them build 4 cars and 2 buses. So ultimately, to figure out how machine A and B relate to cars and buses, you can perform:

$$\begin{bmatrix} 2 & 4 \\ 3 & 2 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 3 & 1 \\ 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}$$

At each stage you should be carefully tracking the meaning of these objects. The columns each represent one of a set of inputs, and each row represents an output. The entry at the $i^{th}$ column and $j^{th}$ row is the quantity of output $j$ produced by $1$ input $i$. Matrix multiplication corresponds to figuring out a new table if you are given two tables where the outputs of one are the inputs of the other.

That is to say, I suggest teaching the linear algebra in a particularly down to earth way, which is unlikely to intimidate students (or other teachers!) with words like "linear transformation" or "vector space".

Perhaps the best is to just say that they are used a lot in computer programming and that is will make sense in a couple years. And then...don't kill yourself or rhe students on making them master them. Just do a minimum and move on.

– quid Feb 01 '19 at 13:58