The concept of an inverse operation itself is a bit tricky. Often we consider arithmetic operations to be binary operations:

$\DeclareMathOperator{\add}{add}$

$\DeclareMathOperator{\subtract}{subtract}$

$$\add(a,b)=a+b,$$

$$\subtract(a,b)=a-b.$$

This is the view we take when we make statements like “addition is commutative,” which is the same as saying $\add(a,b)=\add(b,a)$. However, in this view, addition and subtraction are not inverses of each other. Subtraction does not take the output of addition and return the inputs.

To make sense of the statement that subtraction is the inverse operation of addition, we need to view arithmetic operations as unary operations or single-variable functions:

$$\add_a\!(x)=x+a,$$

$$\subtract_a\!(x)=x-a.$$

In this view, it’s true that $\add_a\!$ and $\subtract_a\!$ are inverses. They undo each other. This is why I prefer to tell students that “subtracting $a$ undoes adding $a$.”

However, there’s a problem. We’ve defined $\subtract_a\!(x)$ to mean “subtract $a$ from $x$.” But what about the operation “from $a$ subtract $x$?” From the binary-operation perspective, this is just $\subtract(a,x)$ instead of $\subtract(x,a)$. But from the unary-operation perspective, this is a completely different kind of operation:

$$\operatorname{subtractfrom}_a\!(x)=a-x,$$ and it is actually it’s own inverse. Suppose we have a bottle of water that has volume $a$ and we spill an unknown volume $x$. How can we recover the information of how much we spilled? We can take the remaining volume and subtract it from the original volume, $a-(a-x)=x$.

This demonstrates that a non-commutative binary operation has two types of associated unary operations, and they have different inverses. The same is true for division. “Divide $x$ by $a$” and “divide $a$ by $x$” are different functions of $x$ with different inverses. The same is also true for exponentiation, and language for distinguishing the two kinds of functions already exists.

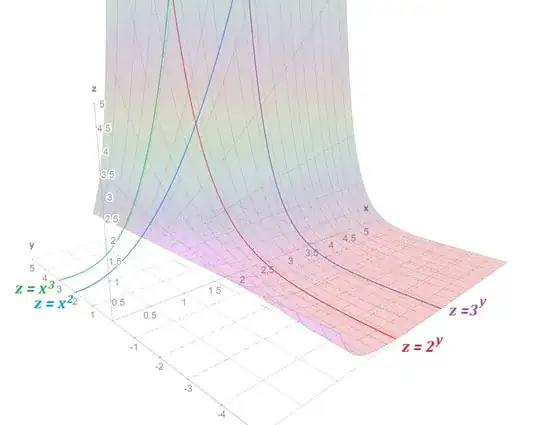

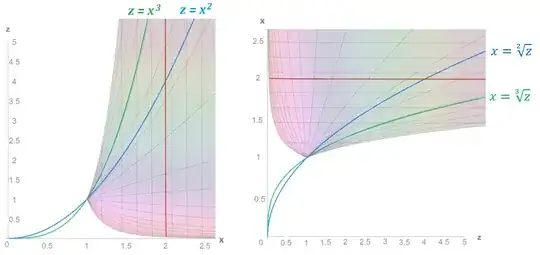

The functions

$$\operatorname{power}_a\!(x)=x^a$$

are commonly known as power functions. Their inverses are other power functions, $(x^a)^{1/a}=x$. When $a$ is a positive integer, $x^{1/a}=\sqrt[a]{x}$ is also called a root function.

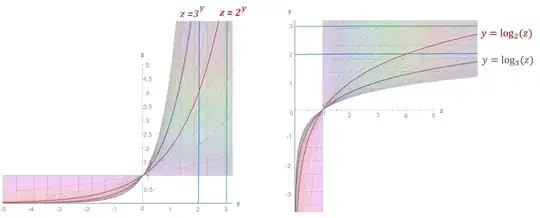

The functions

$$\exp_a\!(x)=a^x$$

are commonly known as exponential functions. Their inverses are logarithmic functions, $\log_a\!(a^x)=x$.

I have to explain this frequently to students in single-variable calculus who are learning derivative rules. Power functions and exponential functions both involve exponentiation, but they are fundamentally different functions with different derivatives:

$$\frac{\mathrm d}{\mathrm d x}x^a=ax^{a-1},$$

$$\frac{\mathrm d}{\mathrm d x}a^x=a^x\ln a.$$

The mnemonic I give them is that “$a^x\!$ is an exponential function because the variable is in the exponent.”