I personally think all of these real world examples do a pretty poor job of helping students form an understanding of implication which is both accurate and useful in forming arguments.

For instance,

- False implies False "If the moon is made of cheese, then I am the Pope".

- False implies True "If the moon is made of cheese, then the moon is not made of cheese".

- True implies True "If 1 + 1 = 2, then in nineteen ninety eight the Undertaker threw Mankind off hеll in a cell and he plummeted sixteen feet through an announcer's table."

These all highlight the fundamental lack of "relevance" between the antecedent and consequent of an implication. There have been attempts to fix this such as https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relevance_logic.

Since these kinds of examples are just as "valid" as the more "sensible" ones you are coming up with using rain and clouds, they must also be accepted by the student for them to have a truly robust model of material implication.

My own hot take is to introduce introduction and elimination rules without mentioning the truth table. These rules are motivated by the following interpretation:

Interpretation: The implication $p \implies q$ is true exactly when given a proof of $p$, we can produce a proof of $q$.

Introduction rule: to argue that $p \implies q$ is true assume we have a proof of $p$ and argue $q$ relative to that assumption.

Elimination rule: A proof of $p$ and a proof of $p \implies q$ together constitute a proof of $q$.

These are the things which are useful for actually doing and using mathematics. The truth table is really not. It is a distraction.

I would focus on using and proving sensible mathematical implications for a long time before discussing truth tables. Things like "For all integers x, if 15 divides x then 5 divides x".

I would also define absurdity by $\bot \implies p$ for all statements $p$. This definitely requires some motivation (such as $1=0$ implying both other absurd statements like $2=0$ as well as true statements like $0=0$: the proof of the first is to multiply both sides by 2 and the second by 0).

You can also mention that this definition of absurdity permits a uniform treatment of the proof of quantified implications. For instance in the proof of "For all integers x, if 15 divides x then 5 divides x" we take an arbitrary integer $x$ and then argue that $5$ divides $x$ under the assumption that we have a proof of $15$ dividing $x$. If $x = 45$ this proof will do a beautiful job of showing exactly how to take the proof that 15 divides 45 (namely demonstrating that for $k=3$ we have $45 = 15k$) and turning it into a proof that $5$ divides $x$ (namely $ j= 3k = 9$ will work to show that $45 = 5j$). However if $x = 17$, and we still want "the same argument to work" we need to accept that a false premise can lead to the conclusion we desire.

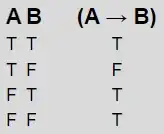

After getting a lot of experience proving honest mathematical theorems using the introduction and elimination rules I would introduce truth tables as a kind of "algebraic shadow" of our reasoning processes. It is an arithmetic of truth, but does not fully capture the subtleties.

Then the rows of the truth table become fairly intuititive: $\bot$ implies everything, if a statement is "true" then it ``proves itself'', so a valid proof of $q$ starting from an assumption of $p$ is to just state $q$, and it should be evident that there is no valid way to argue a false conclusion from a true premise.

I also think that relying on excluded middle as heavily as you do in your proof is a mistake. I try to avoid excluded middle whenever possible, and I would certainly not want to wed it to my fundamental understanding and motivation for implication.

Px⟹Qxis implicitly universally quantified (∀x), that is, not realising that mathematical implications are predicate-logic implications rather than the PL implications they've just encountered in their Discrete Maths class. – ryang Apr 02 '23 at 05:56