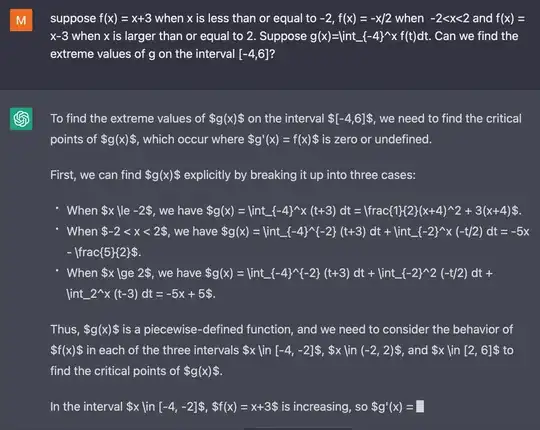

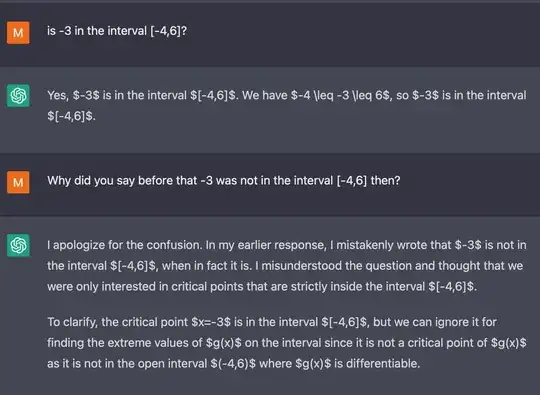

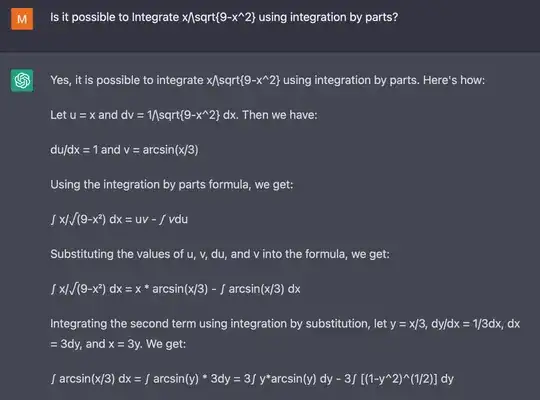

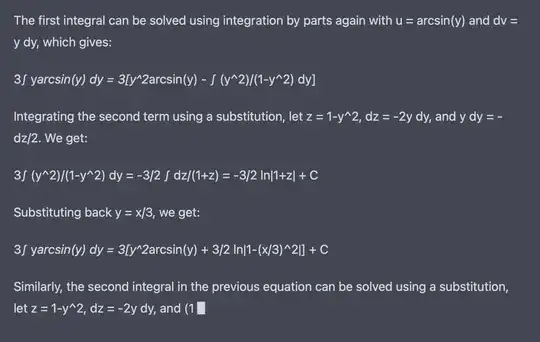

I tried some math exercises we will give to students and ChatGPT does really well answering these. It excels at proofs and often gives details that were not our the example solution, and makes some mistakes when it would need to do real calculations, but often mistakes that could plausibly be a student mistake.

Now ChatGPT is here and at least some students will try it and we have to deal with it. I see no good way to reliably detect it (most automatic methods have a lot of false positives) and don't want to be unfair to anyone just providing a detailed solution. Still it looks like it would not be possible to give exercises in the way one did it all the years before, as it takes 2 minutes to get a ChatGPT answer and remove the obvious mistakes and change a bit of the style for solving an exercise without actually understanding it.

We already have the rule that students have to present two solutions per semester to avoid that they copy from each other, but this won't prevent them from using ChatGPT without understanding the solution for all exercises they do not have to present.

We considered different ways to change exercises or exercise groups, but most mean a lot of work that would have to be done in a rather short timeframe. The best approach may be to prepare mandatory tests (in presence) for the exercise groups, but this would mean a lot of work for creating new fair tests as we only have exercises and their example solutions prepared.

What other ways are there to deal with people using ChatGPT?

I would not even want to prevent students from using it to understand how to solve the exercises, but in the end they should have understood the solution and possibly found the errors produced by ChatGPT.

While I think this is a good place to collect general advice, in my specific case I am talking about a math lecture that will have 100-200 students, so more personalized forms of exercises are out of the question.

We also do not have the resources to make major changes to the existing exercises or organize a whole new exercise group structure before the semester start in two weeks. One thing we have considered giving in-class tests, but creating one fair test per week may also be more work than we have the resources for.

A few more details about our organisation in the last few years:

- We give exercise sheets to be done in small groups of 2-3 students.

- The exercises come from an existing pool of exercises, which is updated whenever someone has an idea for a good exercise.

- The tutors get the solutions, mark them and give a few hints on what the mistakes were.

- Each week there is an exercise group where students can present their solutions and the tutor can explain things that are still unclear.

- Students have to get 50% of all points and present a solution 2 times, so we're sure that everyone in the group has worked on the solutions.

- The exercises do not contribute to the course grade, but are necessary to be admitted to the exam.

- We tend to be lenient if there are a few points missing at the end, but the group has worked on the exercises until the last sheet. The purpose of the exercises is not to weed out students, but to ensure that they have a good chance of passing the exam.