The answer to the lede question "Why do we use function composition?" is "Because we do." It is the way that, for historical reasons, the notation developed. It is a convention which developed before a lot of set theory, modern algebra, and category theory came along, and this convention was deeply ingrained long before anyone thought to question it.

From a naïve point of view, I also think that it makes a good deal of sense: if $f(x)$ denotes the application of a function $f$ to an input $x$, then $g(f(x))$ must denote the application of a function $g$ to an input $f(x)$. Reading from left-to-right, we have "$g$ of $f$ of $x$", which we might abbreviate by $(g\circ f)(x)$.

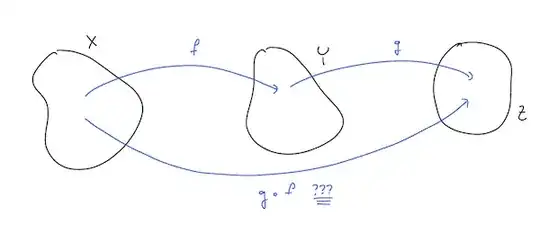

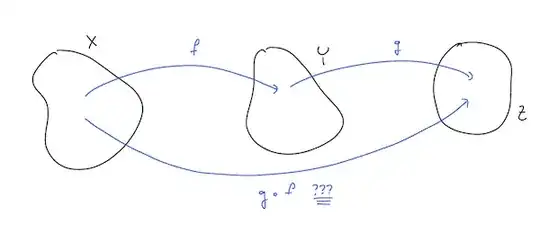

From a more set theoretic point of view, this becomes a little harder to reason about. A typical schematic for functional composition in undergraduate texts looks something like the following:

Reading from left-to-right, we might expect the composite function to be "$f$ and then $g$", which we might want to denote by $f \ast g$ or something similar. But the convention is that this map is $g \circ f$—for historical reasons, maps are applied from right-to-left.

For the most part, this doesn't really cause any problems, but there are some places where you might see some difficulties or a different choice of notation:

Category Theory

In chalk-talks, I have seen one or two category theorists use the notation $(x)f$ to denote the image of $x$ under the map $f$. In this setting,

$$ (x)(f\circ g) = ((x)f)g, $$

which is what we would usually write at $g(f(x))$. So, if you want to compose on the right (as seems "natural"), you should also apply functions on the right.

From one point of view, I suppose that this is a perfectly reasonable convention to adopt (and I kind of wish that we had adopted this convention in the first place), but it is probably a very bad idea to teach this convention to a neophyte.

Differential Operators

Folk who study differential equations will often use notation like $\partial_{xy}$ in order to mean

$$ \partial_{xy} = \partial_y \circ \partial_x, $$

where

$$ \partial_{x} f(x,y) = \frac{\partial}{\partial x} f(x,y). $$

Or should that be

$$ \partial_{xy} = \partial_x \circ \partial_y?$$

There is room for ambiguity here, and authors are well-served to be explicit about what they mean. On the other hand, in most "nice" cases, the derivatives commute, so maybe it doesn't really matter.

Iterated Function Systems

In my own area of research, a common object of study is an iterated function system. Such a system is simply a collection of maps $\{\varphi_j\}_{j=1}^n$ which map some space into itself. The maps are often composed with each other over and over again (hence the "iterated" part of the term), which leads to all kinds of wild notations for composition. One common notation is to take $\mathbf{j} = (j_1, j_2, \dots, j_k)$ to be a tuple of indices, and then write

$$ \varphi^{\mathbf{j}} = \varphi_{j_k} \circ \varphi_{j_{k-1}} \circ \dotsb \circ \varphi_{j_2} \circ \varphi_{j_1}. $$

That is, first apply the map $\varphi_{j_1}$, then apply the map $\varphi_{j_2}$, and so on. However, people mess up this convention all the time. I cannot tell you the number of times that I have seen the convention defined one way, and then applied the other. This doesn't usually cause problems, because the underlying reasoning is generally correct—it is just a problem of transcription—but it can be a concern.

Reverse Polish Notation

I grew up using an HP48 series calculator. These calculators were somewhat unique, in that they implemented computation via reverse Polish notation. The idea is that the arguments of a function are placed onto a "stack", and functions apply to the items on the stack in a "last in, first out" order. So, for example, if I wanted to compute $\sin(\log(5) + 3)$, I might enter the keystrokes

[5] <- this puts 5 on the bottom of the stack

[log] <- the "eats" the 5, and puts log(5) on the bottom of the

stack

[3] <- this "bumps" log(5) up a spot, and puts 3 on the stack

below log(5)

[+] <- this "eats" the bottom two elements of stack, adds

them together, and puts the result on the bottom of

the stack

[sin] <- this "eats" the bottom element of the stack, takes its

sine, and places the result on the bottom of the stack

Written out, the set of keystrokes is "composition in the reverse order", i.e.

5 log 3 + sin

roughly corresponds to writing $(((5)\log, 3){+})\sin$, which kind of looks like backwards composition. Using the standard notation we might write $\sin( {+}(\log(5), 3))$. In both cases, we think of $+$ as a function $+: \mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R}$.

This may look arcane at first glance, but once you get used to it, it is a really convenient way to enter computations into a calculator or computer. It eliminates a lot of errors caused by missing parentheses.

TL;DR

The current convention exists for historical reasons. If we were to start all over again, we might adopt a different convention, and there are good reasons to want to do so. However, the convention exists, is well-established, and you would be doing your students a disservice to introduce an alternative notation.

x // f // gfor $g(f(x))$. It also has theRightCompositionoperator (RightComposition[f, g, h]denotes $h \circ g \circ f$). A textbook I once had wrote $xfg$ for $g(f(x))$, function application being denoted by juxtaposition of an element followed by a function. This is something like Reverse Polish Notation, which some calculators and the PostScript language use. I like the//notation and RPN in programming; I did not like $xfg$ because it looked like multiplication. – user1815 Feb 22 '22 at 18:13