(I was inspired by the comments in this answer to ask this question.)

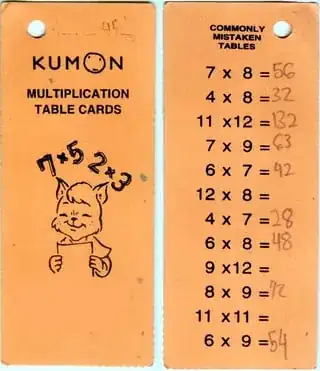

I have some multiplication table cards from Kumon that have a list of commonly mistaken multiplications: $7\times 8, 4\times 8, 11\times 12, 7\times 9, 6\times 7, 12\times 8, 4\times 7, 6\times 8, 9\times 12, 8\times 9, 11\times 11$, and $6\times 9$ (in this order).

I assume that this is based on data they obtained from the numerous children who have answered their worksheets.

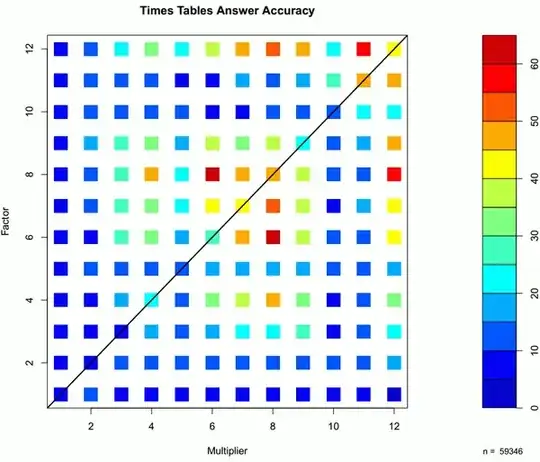

Is there some other source (a study, perhaps) that lists the products of single digits that children usually get wrong?

To this day I have to stop and take a moment to think "is it 54 or 56???"

– ruferd Mar 03 '21 at 14:517 × 8and9 × 6. I had to wait a day to try again, and I've never mixed them up since! – Scott Sauyet Mar 04 '21 at 04:177 × 8and9 × 6(which one is 54 and which one is 56) is so common, that has always been a challenge for me as well, it's probably the only pair I need to really think about rather than just "know". – jcaron Mar 04 '21 at 11:15… for 6×7, I resorted to 6×6+6… why?

… for 7×8, try doubling 7×4… again, why use tricks?

I see how thin a limb I sit on yet why promote theory over simple evidence?

Adam, J W et al clearly show they saw learning times tables not as a rote task but as something to be understood, at which they failed. Of course they did!

Which teacher here doesn't see that children getting any product of single digits wrong is nothing to do with children or numbers and that that leaves… sorry: teaching!

– Robbie Goodwin Apr 29 '23 at 18:34