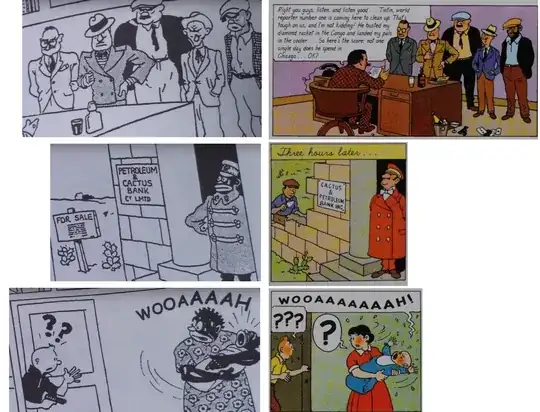

The first efforts to market Tintin to an American readership happened in the early 1960s, in the ill-fated "Golden Press debacle", when, among other things, the American publisher Golden Press demanded the removal of scenes of the consumption of alcohol (what would happen to Captain Haddock?), wanted to rename "Snowy" to "Buddy", and also required the removal of black characters from The Crab with the Golden Claws:

The US censors didn’t approve of mixing races in children’s books, so

the artist created new frames, replacing black deckhand Jumbo with

another character, possibly of Puerto-Rican origin. Elsewhere, a black

character shown whipping Captain Haddock was replaced by someone of

North African appearance.

The effort flopped, however, and the release of Tintin albums in the USA stagnated until the publishing house Atlantic-Little, Brown took over the rights in the 1970s. As the Wikipedia article notes, problems again arose with the depiction of black characters, this time in Tintin in America.

From Thompson's 1991 book Tintin: Hergé and his creation, cited in the Wikipedia article:

The Americans put themselves firmly in the wrong when they refused to

print any frames that pictured black people at all. Outrageously, as

late as the 1960s, Hergé was forced to go over parts of his work and

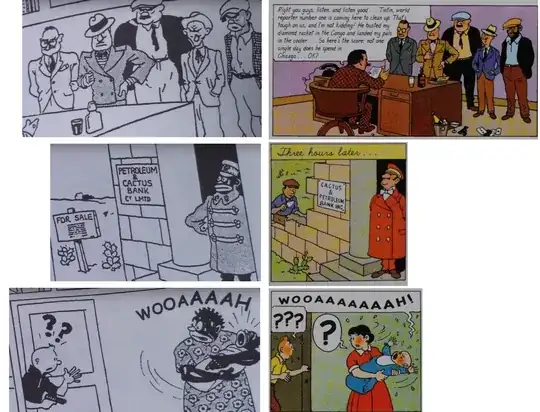

remove black characters. The doorman at the half-built bank in this

same scene was originally black, as were the mother and baby whom

Tintin inadvertently disturbs on page 47.

Micheal Farr's work Tintin The Complete Companion (freely available from the Internet Archive) notes that just three frames were changed:

Hergé returned for a third time to the American adventure for a 1973

edition, when apart from tightening up the formatting of the script by

cutting out whenever possible hyphenated breaks, he made significant

concessions to his American publishers by removing in three cases

blacks from the narrative. They objected to the placing of blacks

alongside whites in a story destined for young readers.

[The album had first been released in black and white in 1932 and been transferred to color, and generally tightened up, in 1946, hence the remark that Hergé returned to it "for the third time"]. The three frames in question are on the first page: when Al Capone address his henchmen, the black man on the far right is changed to a swarthy Italian/Puerto Rican type character in the new version. On page 29 the commissionaire on duty at the "Petroleum and Cactus Bank" was changed from a black to a white man, and on page 47 a mother and her crying baby were changed from black to white.

Although done for bad reasons - presumably as in the 1960s this was done to remove evidence of racial desegregation, although neither Farr nor Thompson explicitly state this, or who required it - it was not wholly a bad thing. The images of black people Hergé drew are rather stereotypical and offensive.

Thompson gives the publication date of the English version of Tintin in America as 1978, post-dating the redrawing, so it seems there was no previous English language version which contained the African-American characters. Some European translations were made earlier, but I have not been able to locate one, to see the African-American characters in a color version of the album.