Believe it or not, this is not an unfamiliar problem for bureaucracies.

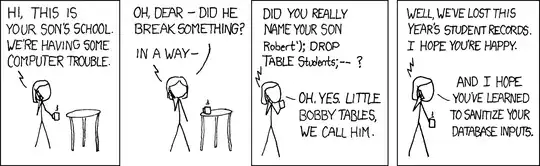

See this for another example in comedy, and a certain style of solution:

Derek (drops lighter) Nippl-e

The standard way of handling it is that bureaucracies have rules about how names must be represented in writing.

In the Anglophone world, a typical requirement is that names be represented only with letters of the English alphabet.

In terms of "legal" names - that is, presumably meaning a name recorded at the registry office upon a standard set of life events like birth, marriage, or death - the registrar (an official employed by the state) may also control the proposed registration of names which he thinks are motivated by mischief or would contribute to mischievous ends.

The string Robert'); DROP TABLE Students;-- is not therefore a person's "name" in an English-based legal jurisdiction. It is not a name firstly because it does not consist only of English letters, and secondly because (even when shorn of the punctuation elements) a registrar could well suspect mischief and therefore refuse the registration of such a name for any official purpose of the state.

In terms of whether entering such a string into a computer system would be criminal, that is likely to be highly dependent on context, including whether it was done with a malicious purpose.

If the purpose of making the entry was not malicious - for example, if some waggish computer programmer chose it as a screen name, and then "damage" was caused (i.e. the computer belonging to the bureaucracy reacted differently than the bureaucracy would have preferred) - then I doubt it would be a criminal act.

There is not in general any requirement for the public operating or making entries into computer systems, when explicitly or implicitly authorised to operate the computer as a member of the public, to understand technical matters or (even if they do understand technical matters) to anticipate how the computer may react adversely to their use.

Nor are they required to understand what opinion the bureaucracy may have on whether certain reactions by the computer are desirable for their ends, and the mere fact that a computer has reacted adversely in the opinion of the bureaucracy which owns and programs it, does not determine the question of whether the operator was engaged in a criminal act by triggering that adverse reaction.

By analogy, if we had a `Robert Jump-Off-Roof Tables" who submitted his name to a bureaucracy, and a human clerk administering records with this name then proceeded to the roof of the building and jumped off, a court may well decide that the result is too remote for the mere submission of that name to be a criminal act.

It might be too remote even if the submission was performed mischievously to see what reaction it provoked amongst the clerical staff, because no reasonable person would think that a clerk should react to seeing such a name by jumping off a roof, even if they did in fact do so. Likewise, if a computer reacts to certain inputs in ways that are unreasonable.