I am trying to fit

ᾰ̓κήκοᾰ (active indicative perfect of ᾰ̓κούω, first person singular)

to the model of

λέλῠκᾰ (active indicative perfect of λῡ́ω, first person singular),

wherein the word breaks down to:

λέ-λῠ-κ-ᾰ, or

reduplication - stem - tense suffix - personal ending.

(Please let me know if I got that terminology wrong already.)

QUESTION

Am I right to do it as follows?

ᾰ̓κ-ήκο-ᾰ, or

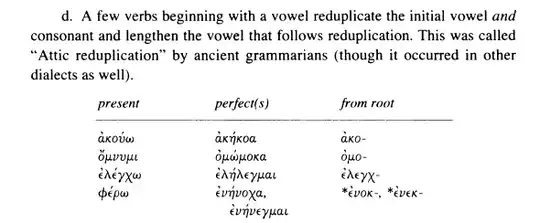

reduplication - stem - [no tense suffix] - personal endingTo get that far, I relied on Mastronarde's Introduction to Attic Greek, which states:

Is there any basis to think that the original reduplication was of the initial vowel and consonant and the second vowel? The idea would be that, for example:

ᾰ̓κο-ᾰκο-ᾰ → ᾰ̓κ-ήκο-ᾰ.

Actual attested earlier forms of the ᾰ̓κο-ᾰκο-ᾰ sort would be the best kind of answer.

Another good answer would give a word that began with a vowel - consonant - consonant sequence, but received an Attic reduplication with the 'lengthening' of the second vowel (which would, as it were, refute the theory being proposed). Note that all four of Mastronarde's examples begin with a V-C-V sequence (tempting one to the theory).

BACKGROUND

As an aside, the theory seems to represent my mind's trying to reduce the number of primitive devices (already too many). Reduplication of some number of initial letters (up to three) seems like fewer such devices than reduplication or reduplication plus lengthening.