In this answer to a question about the preciseness of Latin, there is a quote from from Frederic Taber Cooper's Word formation in the Roman Sermo Plebeius (1895):

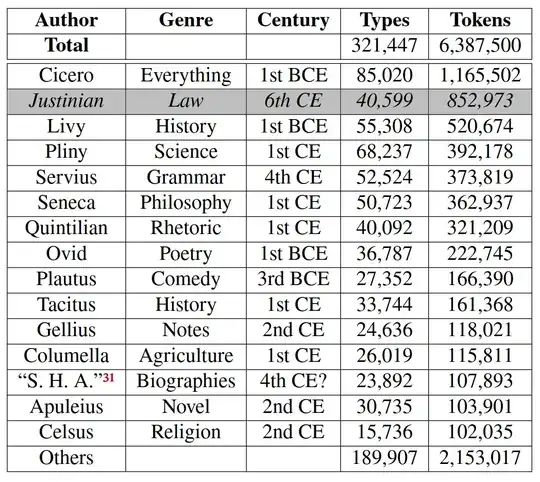

There were, as Cicero himself has pointed out, three ways in which the deficiencies of the vocabulary could be supplied; either by the transfer of a Greek word bodily into the Latin, by the use of an existing Latin word in a new sense, or by the formation of a new word. But in the classic period the use of foreign words was felt to be contrary to good taste and was accordingly avoided as far as possible, while unusual expressions, either archaisms or neologisms, were severely discountenanced. Even Cicero, who did more than anyone else toward giving currency to new formations, introduced many excellent and sorely needed words with hesitation and apology. Quintilian, while admitting that new words must occasionally be risked, says frankly that even when received into the language they brought little credit to their author, and if rejected led only to ridicule; and Gellius, still more emphatic, declares that new and unknown words are worse than vulgarisms.

This extreme attitude, however, had become untenable long before the time of Gellius; a point had been reached where growth of vocabulary was essential to the life of the language. But it was a natural consequence of such conservatism that no process existed for forming a literary vocabulary possessing distinctive features which might stamp it as a cultured product; no scientific nomenclature corresponding to the -ologies, -isms, and -anas of our own language; there was not a single suffix which could be regarded as distinctly classic, and which was not comparatively more abundant in authors of inferior Latinity.

If Latin was more resistant to new formations and vocabulary as compared to other languages, did this mean that Latin was more mutually-intelligible over time as well? For the purposes of this question I'd prefer to limit this to written Latin and avoid sound changes.