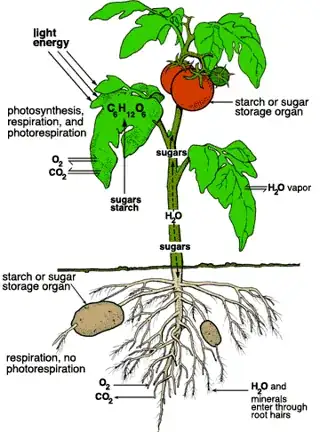

If you spend a little time gardening, you soon become aware that plants store energy in their roots, which they collect from the Sun through their leaves. By the end of Autumn, perennials usually have thick roots—the best time for making them into tinctures. In the Spring, many perennials produce new stalks, flowers, and leaves in a burst of growth which depletes their roots, leaving them shriveled up and needing a summer to replenish. Biennials produce no flower or seed their first year. Instead they produce only leaves to gather sunlight to store energy in their roots, which they expend in their second year to flower and reproduce. Some annuals, like potatoes, store up energy in tubers underground, which then power the growth of new stalks and leaves—or supply energy for us when we eat them. There are yet more variations, but you get the idea: plant life is a yearly rhythm of collecting energy, storing it, and using that energy to fuel the start of the next cycle.

I figure the ancients and medievals spent a lot of time gardening or doing its larger-scale variant, agriculture, so all of the above must have been even more obvious to them. How, then, did they describe the yearly flow of energy from Sun to leaves to roots to new plants? What did they call the thing that the plants accumulate and store in their roots? Or did they not think of it this way at all?