A good discussion and summary of this interesting question can be found in this work: VESTER, ELSELINE (1991). "Reflections on the gerund and gerundive". In Robert Coleman (ed.). New Studies in Latin Linguistics. 295-310. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Vester points out that the gerund cannot take objects in the following contexts. In these cases the use of gerundive is quite pervasive (but see below for some relevant exceptions).

dative: aptus scribendo (*epistulam)

in+ablative: in scribendo (*epistulam) obdormivit

ad+accusative: paratus ad scribendum (*epistulam)

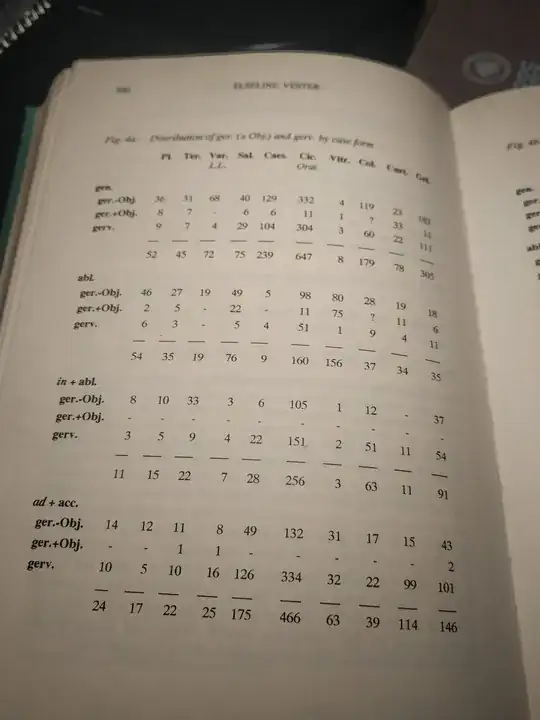

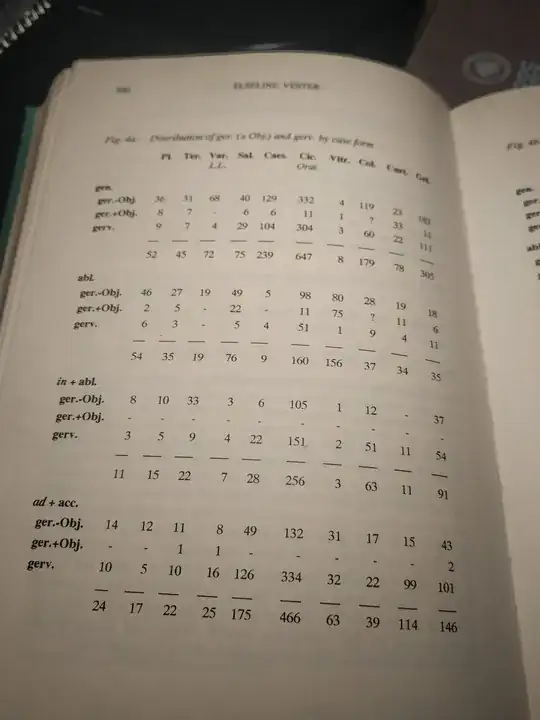

As for your (sub)questions "How strong is the rule? Do we have strong evidence that the Romans always obeyed this rule? Do ancient authors always follow this rule?", the prohibition of using objects with gerunds is, for example, very strong in in+ablative and ad+accusative contexts across many authors of different periods (and for me this is a very interesting issue: there must be a grammatical (i.e. not merely stylistic) explanation accounting for the consistent absence of objects in these particular contexts, an explanation that, by the way, is not provided by a functionalist linguist like Vester). As for other cases, the norm varies across authors: e.g., the gerund in ablative often takes objects in Vitruvius, less so in Sallust, and much less so in Cicero('s speeches/orationes). See some relevant data and percentages in Vester (1991). Here is a useful information extracted from her Figure 4a:

DISTRIBUTION OF GERUND (+/- OBJECT) AND GERUNDIVE BY CASE FORM (corpus: Pl(autus), Ter(entius), Var(ro Lingua Latina), Sal(lustius), Caes(ar), Cic(ero Orationes), Vitr(uvius), Col(umella), Curt(ius), and Gel(lius)).

As is well-known, it is often stated in many Latin grammars that one can say/write cupidus videndi urbem (gerund) and cupidus videndae urbis (gerundive). However, when one looks at the data & percentages, one realizes that there are some important differences across authors of different periods: the usage of gerund+object in this context is more typical of Early Latin than of Classical Latin, where the gerundive is by far much more used.

Note also that the strong statement in your post "one cannot say aquam bibendum est" is not fully correct: there are some few attested examples of this usage: agitandum est vigilias (Pl. Trin. 869); aeternas poenas in morte timendum est (Lucr. 1, 111), i.a. See also some further discussion & comments in this post. See also Vester (1991: 297): "it is evident that scribendum is a gerund in mihi epistulam scribendum est, but for some scholars it is less evident in mihi scribendum est", where most of them assume it is a gerundive (NB: Bolkestein, who has been considered as the second authority after Pinkster in functional approaches to Latin linguistics, assumes it is a gerund). For a more detailed analysis of this issue, see Miller's (2000) formal/generative approach.

To conclude, if one is not interested in philological differences of usage (e.g., the usage of non-prepositional ablative plus object is typical of Vitruvius but not of Cicero, the usage of aquam bibendum est is not typical but it is found in ...), the simplified rule for learners/"speakers" of Latin is to use the gerundive instead of the "gerund plus object" (except under the well-known circumstances pointed out by TKR and Joel Derfner. For a nice summary of these circumstances, i.a., I recommend the reading of the excellent chapter XVII "The Gerund and Gerundive" (pp. 157-166) by E. C. Woodcock (1959). A New Latin Syntax. London: Methuen).