Knowledge of the specific fact that $(\sin x)' = \cos x$ actually predates the general knowledge of calculus and derivatives. It was known in the following form: that for very small $\Delta x$, when you increase $x$ to $x + \Delta x$, the increase in value of the sine, from $\sin x$ to $\sin (x + \Delta x)$, is proportional to $\Delta x$ times $\cos x$. In other words, that

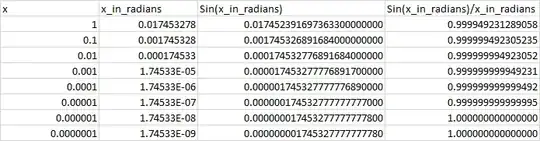

$$\frac{\sin (x + \Delta x) - \sin x}{\Delta x} \approx \cos x$$

The approximation being exact in the limit as $\Delta x \to 0$ is of course the modern definition of the derivative.

This happened historically in Indian mathematics, where Muñjala (around 932), Āryabhaṭa II (around 950), Prashastidhara (around 958) all give the above rule for calculating $\sin(x + \Delta x)$, and an explicit geometric reasoning / justification is given by Bhāskara II (around 1150) in his Siddhanta Shiromani. I have not found a perfectly good reference to these, but you can start with the following article:

- Use of Calculus in Hindu Mathematics, by Bibhutibhusan Datta and Awadhesh Narayan Singh, revised by Kripa Shankar Shukla, Indian Journal of the History of Science, 19 (2): 95–104 (1984). (PDF)

It was first pointed out by Bapu Deva Shastri in Bhaskara's knowledge of the Differential Calculus, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Volume 27, 1858, pp. 213–6.