Equally short as well as probably controversial answer: the War on Drugs, institutionalised racism, an increasingly intoxicating political climate rife with taboos based on moral panic, politics of fear, a general conservative backlash, as well as the privatisation of prisons can account for these numbers. Distilling all these effects piling up onto another into one reason: That makes it a political decision, however irrational or cruel it was.

By the mid-1980s, a few penologists, I among them, began to speculate that what had by that time become a 15-year prison population run-up was a trend that had to be nearing an end. We were alarmed at a prison population growth spinning out of control, and because we could find no rational explanation for the growth, unprecedented at that time, we came to the conclusion it was a politically spawned spurt that had about run its course. If you had told us then that the growth in imprisonment numbers was not even half finished, we would have been horrified at the prospect. A generation ago, nobody could have foreseen what was about to take place in U.S. penal policy for the next 35 years. What would have appalled us then to contemplate should appall us now to experience.

Todd R. Clear: "Imprisoning Communities. How Mass Incarceration Makes Disadvantaged Neighborhoods Worse", Oxford University Press: Oxford, New York, 2007.

The longer version

This increase is unrelated in its proportions to any increase in criminal activity that is punished with incarceration.

In the past 30 years, the United States has come to rely on imprisonment as its response to all types of crime. Even minor violations of parole or probation often lead to a return to prison. This has created a prison system of unprecedented size in this country.

The US has less than 5% of the world’s population but over 23% of the world’s incarcerated people.

The US incarcerates the largest number of people in the world.

The Wikipedia page on the causes cites Jeremy Travis: "The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. National Research Council, 2014, p. 40 with just a few factors: –Increased sentencing laws – Economic and age contributions – Drug sentencing laws – Racialization – Prison privatization – Editorial policies of major media – Citizenship statistics

That is quite a tough nut to crack. How is are these factors explainable? One side prefers the simpler explanations:

Criminologists and legal experts here and abroad point to a tangle of factors to explain America’s extraordinary incarceration rate: higher levels of violent crime, harsher sentencing laws, a legacy of racial turmoil, a special fervor in combating illegal drugs, the American temperament, and the lack of a social safety net. Even democracy plays a role, as judges — many of whom are elected, another American anomaly — yield to populist demands for tough justice.

Mr. Whitman, who has studied Tocqueville’s work on American penitentiaries, was asked what accounted for America’s booming prison population.

“Unfortunately, a lot of the answer is democracy — just what Tocqueville was talking about,” he said. “We have a highly politicized criminal justice system.”

Adam Liptak: "Inmate Count in U.S. Dwarfs Other Nations’", Ney York Times, April 23, 2008.

So, one of the most dominant explanations is that the majority of the electorate actually wants to see people in prison. That may not be overly rational, but it is a choice, even if many involved in this process did not see and still do not see any choice in that matter. Whether that is either an appropriate description or a reasonable approach to the problem of crime will remain in the debate for quite some time.

“The way prisons are run and their inmates treated gives a faithful picture of a society, especially of the ideas and methods of those who dominate that society. Prisons indicate the distance to which government and social conscience have come in their concern and respect for the human being.” (Milovan Djilas, cited from Gottschalk 2006)

There are basically a few fundamentally different perspectives to look at this problem – of either crime or incarceration: cause and effect, stimulus and response, intervention and result, intent, incentives and unintended consequences, spurious correlations and ideology.

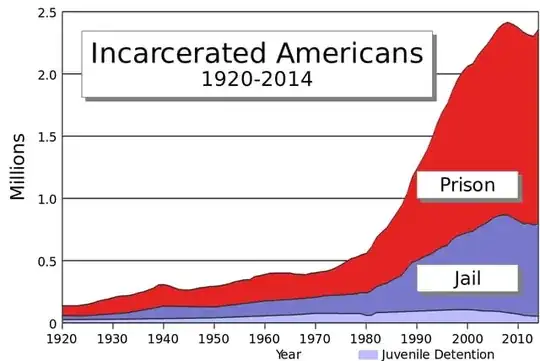

A simple timeline (if you prefer charts):

1971 Nixon declares War on Drugs

1973 New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller enacts toughest drug laws in the nation, starts Mandatory sentencing

1973 Nixon creates DEA

1980 CNN goes live

1982 Reagan intensifies War on Drugs

1983 Corrections Corporation of America founded

1984 privatisation of prisons

1984 Sentencing Reform act (minimum sentencing)

truth-in-sentencing

1986 Anti-Drug-Abuse act

1993 3-strikes rule first in Washington (Initiative 593, life without parole for 3rd time offenders)

1994 3-strikes-rule in California, toughest and most often used

1994 Clinton's Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act

1996 Clinton's welfare reform decreases chances for formerly convicted drug offenders

There are just no scientific studies to show that that "tough on crime" reduces crime, it's either uncorrelated or even in an inverse relationship. But there are numerous studies that show that "tough on crime" is a prerequisite for candidates to not reduce votes in elections. Voters demand irrational politics.

The TV station is just a symbol here. It is not the station itself, but the trend to more news, less information, distorted views of reality and consequently fear and mass-hysteria about crime. There are numerous scociological and psychological factors that indicate that the sensationalist sex&crime reporting continues or even intensifies, while the rate of crime, and violent crime especially continue to drop. The battle for a reduction of lead in paint and gas seems to better explain dropping crime rates than toughening of laws and sentences. But the electing public does know neither that crime rates drop nor that laws or just a small factor for prevention. And many just do not care as they opt for a revenge punishment in every case.

When progressivism’s promise of a science and government cure to the crime problem failed to materialize, society was stripped of all hope and expectations. As a result, frustration, rather than reason, determined crime control policy. Tucked away in current formulations [of crime control policy] is evidence of the resignation and confusion that presumably typifies modern society.

William Lyons and Stuart Scheingold state that “the anxieties associ- ated with unwelcome social, economic, and cultural transformations generate anger, and punishment becomes a vehicle for expressing that anger.”5 Katherine Beckett maintains that the pro-prison movement served as a channel to express the diffuse anxieties associated with the breakdown of gender and racial hierarchies: “Economic pressures, anxiety about social change, and a pervasive sense of insecurity clearly engender a great deal of frustration, and the scapegoating of the underclass has been a relatively successful way of tapping and channeling these sentiments.”6 This scapegoating took the form of irrational demands for more severe sentencing.

Bert Useem & Anne Morrison Piehl: "Prison State

The Challenge of Mass Incarceration", Chapter Two: "Causes of the Prison Buildup", Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, New York, 2008.

When trying to analyse this with a more comprehensive outlook, things get complicated in the details, but clear in the numbers, with prominent reasons hard to deny, but little perspective on how that inevitability came to be inevitable, or solvable:

State and federal incarceration rates grew by over 200 percent between 1980 and 1996. The dominant factor is drug offending, which grew by ten

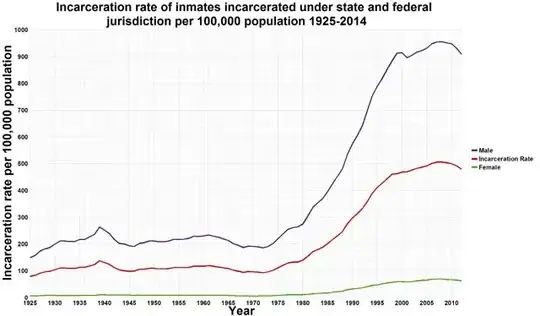

times, followed by assault and sexual assault. The growth can be partitioned among four stages: offending rates; arrests per offense; commitments to prison per arrest; and time served in prison, including time served on parole recommitments. The growth in incarceration for drugs is driven most strongly by growth in arrest rates, then by commitments per arrest; there is some increase in time served, but only in the federal system. For other offenses, there are no changes in arrests per reported offense and a net decline in offending rates. Over the full period, the growth in state incarceration for nondrug offenses is attributable entirely to sentencing increases: 42 percent to commitments per arrest and 58 percent to time-served increases. Recently, new court commitments and parole violations have flattened out; the dominant contributor to current growth for all the offenses examined is time served. Incarceration rates rose faster for women (364 percent) and minorities (184 percent for African Americans and 235 percent for Hispanics) than for men (195 percent) and non-Hispanic whites (164 percent).

All of these considerations inherently involve the question of the value received by the public as a result of current incarceration rates. It might have been reasonable to expect crime to have declined as a result of the quadrupling of the incarceration rate (Blumstein 1995c), but no such connection has been displayed. There certainly have been attempts to link the decline in crime during the 1990s to the growth in the prison population,"0 but any such argument must also explain why crime rates increased in the 1970s and the late 1980s while prison

populations grew at the same rate as they did in the 1990s.

Of course, so complex an issue as the relationship between crime and punishment cannot be addressed through so simplistic an analysis as a negative correlation between the two very aggregated time series of crime rates and incarceration rates. That has been attempted, often

with significant manipulation, to make a rhetorical point.

The aggregation of the two time series ignores the fact that very different factors could be affecting each one, thereby making the correlation more spurious than causal. For example, as the evidence in this essay makes clear, the growth in incarceration rate has been very strongly affected by drug enforcement policy, but drug offending does not enter into any of the measures of crime rates. Discerning the relationship between sanctioning policy and crime rates is the focus of considerable research in the areas of deterrence and incapacitation, requiring careful measurement and control for the many factors other thaincarceration that affect crime rates (Blumstein, Cohen, and Nagin 1978; Cook 1980; Nagin 1998).

Furthermore, in order to establish sensible policy, benefits obtained from shifts up or down in sanctioning policy must be examined. Calling for particular attention is the massive incarceration of drug offenders, the largest group in prison. Incarceration of even three hundred thousand drug offenders does little to reduce drug sales through deterrence or incapacitation as long as the drug market can simply recruit replacements for those scared out of the business or locked away in prison (Bourgois 1989; Reuter, MacCoun, and Murphy 1990). But the analysis cannot stop there. To the extent that some of those drug offenders would have been committing other crimes on the street that are not replaced, such as interpersonal violence, their imprisonment could be contributing to the aggregate incapacitative effect of incarceration.

It is also possible that crime rates did not decrease during the 1980s while prison populations soared because the nation's level of criminality (as measured by the number of active offenders or their rate of committing crimes) would otherwise have increased during this period. If that were the case, then the growing incarceration may have kept the crime rate from ballooning dramatically. Alternatively, it could be that incarceration is far less effective than the public thinks it is or than we would all like it to be for the considerable investment it requires. People who spend time in prison have considerable difficulty functioning in the legitimate job market when they come out (Freeman 1994, 1996). These difficulties, combined with the criminal skills they develop and the connections they make while in prison, may increase the likelihood that they persist in criminal careers.

Knowledge to address these questions responsibly, especially in deal- ing with drug offenders, still remains unavailable. As the nation's expenditures for incarceration increases from the current level of nearly $25 billion per year, the cost of that ignorance will continue to grow. We need to know the benefits of incarceration in terms of the incapacitation and deterrence of crime. We need to find better guidance for focusing incarceration on those offenses and those offenders that represent the most serious threats and for whom incarceration will achieve the greatest crime control benefits. And we have to weigh these benefits against the number of lives disrupted (now totaling more than 1.7 million individuals in America's prisons and jails) and the families and communities-especially minority communities-disrupted by large numbers of individuals being extracted and kept in prison. Better understanding of these issues is crucial for the development of informed policy.

Alfred Blumstein & Allen J. Beck: "Population Growth in U.S. Prisons, 1980-1996", 26 Crime. & Just. 17, 1999.

The United States presents a fundamental challenge to Durkheim’s claim that punishment will grow milder as societies modernize. While continental Europe has been moving in a milder direction by fits and starts, the United States certainly has not. David Garland likens the infliction of punishment by the state on its citizens to “a civil war in miniature.” If this is so, then the United States is currently engaged in a massive war with itself.

With so many millions somehow enmeshed in the criminal justice system, the penal policies of the United States have a certain taken-for- granted quality. Just as it seemed unimaginable thirty years ago that the United States would be imprisoning its people at such unprecedented rates, today it seems almost unimaginable that the country will veer off in a new direction and begin to empty and board up its prisons. Yet as Mathiesen reminds us, “major repressive systems have succeeded in looking extremely stable almost until the day they have collapsed.”

Marie Gottschalk: "The Prison and the Gallows. The Politics of Mass Incarceration in America", Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, New York, 2006.

Per popular demand: The perverse incentives of private prisons, Economist 2010

Moreover, contractors have every incentive to make themselves seem necessary. It is well-known that public prison employee unions constitute a powerful constituency for tough sentencing policies that lead to larger prison populations requiring additional prisons and personnel. The great hazard of contracting out incarceration "services" is that private firms may well turn out to be even more efficient and effective than unions in lobbying for policies that would increase prison populations.

One objective a humane crime punishment system should have is the rehabilitation of inmates, that return as reformed members into society. The incentives for private prisons are maximising profit and that means a revolving door is financially welcome effect of doing much less to prevent recidivism of released prisoners. Among other things this desire for "repeat customers" is compounded with ever increasing demands fro harder, longer sentences. This effect is the exact diametrical opposite to the goal of reducing crime. Private prisons increase crime. Privatisation of prisons was a crime in itself.

From Megan Mumford et al.: "The economics of private prisons" Brookings, 2016 (longer PDF):

The correctional system aims to protect the public by deterring crime and removing and rehabilitating those who commit it. Traditionally, the government has funded and operated correctional facilities, but some states and the federal government have chosen to contract with private companies, potentially saving money or increasing quality.

In addition, there may be differences in the effectiveness of public and private systems in promoting rehabilitation and minimizing recidivism. These differences may arise due to the incentives provided in private prison contracts, which pay on the basis of the number of beds utilized and typically contain no incentives to produce desirable outcomes such as low recidivism rates. The 2016 Nobel prize-winner in Economics, Oliver Hart, and coauthors explained that prison contracts tend to induce the wrong incentives by focusing on specific tasks such as accreditation requirements and hours of staff training rather than outcomes, and noted the failure of most contracts to address excessive use of force and quality of personnel in particular.