This is a question more about culture than language specifically but I hope it is still appropriate here.

It's a common topic in current media commentary (in English) to complain about the problems with younger people. They don't want to work, they're lazy, men are becoming more effeminate and women more masculine, they all drink too much.

But it is somewhat naive to say current. This has been a trend for a while. Our parents may say it about our generation, but their parents said it about their generation. And it keeps going.

This has been a trend through the ages. There is an apocryphal story about Socrates' such complaints.

Here are some examples in English (source) and here:

- (1937) "Nobody wants to work anymore".

- (1916) "Nobody wants to work as hard as they used to".

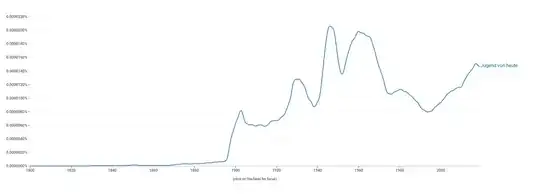

My question is: Is there a historical trend for people to complain about the laziness of youth, generation after generation, in German culture and media?

All the examples in that image are from US newspapers, but I am just so unaware if there is a similar possible situation in German culture and language for people to complain so openly. But there still may be examples in literature that I am also unaware of.

If you can, please give quotes from newspapers, books, or other media from before 1900.