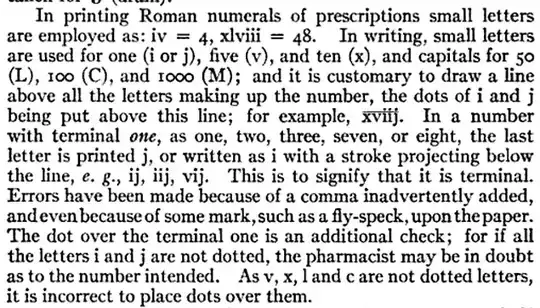

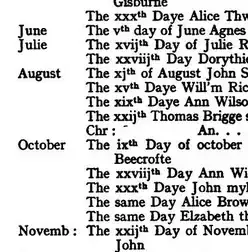

While using an old (1907) book of transcriptions (on-line) The Parish Register of Gargrave in the County of York , I was puzzled by the number of dates recorded in the 16th and early 17th centuries that could be read easily as Roman numerals except for the addition of a j at the end.

The pattern (if there is one) seems to be that if the number would ordinarily end with i then j is appended, but if it ends with v or x then there may be no extra character before the ordinal superscript (but in one case, there is!).

I thought this may be a style quirk of a particular clerk, but now I am seeing it in other sources (but all Yorkshire based and pre-1700, because that is what I am reading at the moment).

- Is this a real phenomenon or just a coincidence?

- How widespread was the practice?

- What on earth did it mean? Why did they do it?