Part of the reason for confusion here may be that genealogy software tends to be very person-centered, and it's easy to fall into a person-centered workflow. We tend to think of gathering information about a person, then adding it to our database, then attaching the source citation as an afterthought.

It's natural to take a person-centered approach as we are looking for sources -- the reason we collected it in the first place is because we thought it might belong to one of our people. But once we roll up our sleeves and analyze the source itself, it's important to switch things up and learn more about the nature of the source itself, so we can understand what the source is telling us.

Principles of Evidence Analysis

If you look at the Evidence Analysis Process Map from Elizabeth Shown Mills' Evidence Explained (see QuickLesson 17: The Evidence Analysis Process Map), you'll see three critical elements mapped out: SOURCES, INFORMATION & EVIDENCE. Each of these three elements can be broken down into three different classes, which is why you'll see Mills' map referred to sometimes as "the 3 x 3".

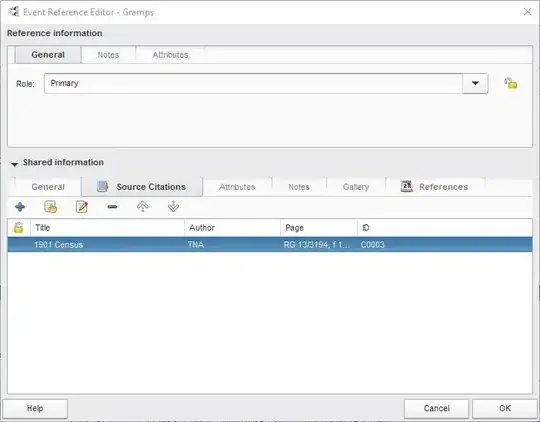

In a source-focused approach, you start with a source, create the source citation for the source first, and then extract all the information inside the source, analyzing it as you go. There are two basic reasons to do this -- first, to understand the nature of the source, and second, to remember where the information comes from (both for ourselves, and so we can point other people to the source if they need to check our work or find the source, too).

The source (document, etc.) is the container -- the information is the contents. For evidence, I'll quote Mills rather than paraphrase:

Evidence is our interpretation of information that we consider relevant to a particular research question.

George G. Morgan gives a good example of working from a source in his blog post Three Genealogical Exercises -- see the section Dissecting Obituaries:

First, I read the obituary in full. Next, I use a pencil to underscore

individual pieces of information in the obituary that point to some

resource that may or will be of genealogical value. The obvious items

are name, gender, age, residence, life events, place where a funeral

or memorial service is scheduled, names of officiating clergy, place

of interment, and names of any survivors. Other information may

include occupation, name of spouse(s), sibling(s), place of birth,

life events, military service, church affiliation, occupation, and

more.

I prepare a list that includes each and every one of these underlined

clues. Underneath each one, I notate 1) what information that clue can

provide; 2) what records might exist of the fact or clue; and 3) where

the record(s) would be held. A typical short obituary usually has at

least a dozen such clues to records. I then use telephone and city

directories, the Internet, and other resources to determine the

location that I would contact for more information. The exercise takes

about thirty minutes or less for each obituary.

To do the same analysis for the census, for US Census records, I often use these links as a prompt:

There is much more information that can be gleaned from a census record, especially from the really nosy 20th-century US Federal census returns, than simply recording the basic information of name, age, location, etc. In a source-centered approach to research, whether to record a source as a source is never a question -- sources always get recorded, and if you use the information in them, you always record where the information came from.

That being said, asking if you should record an event for a census is a good question. But -- which event to use?

Census versus Residence

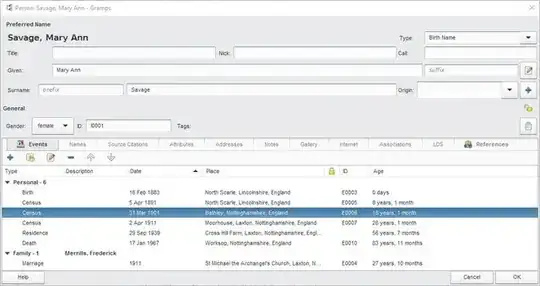

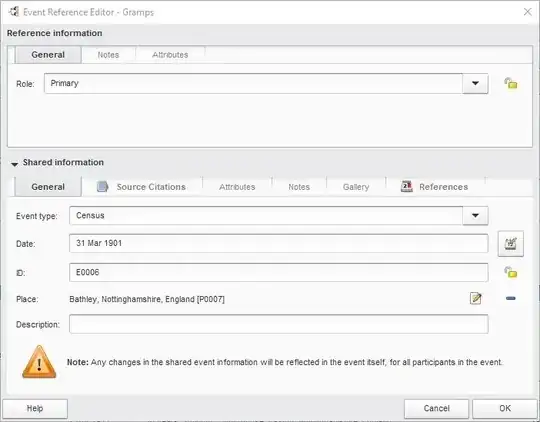

I haven't used Gramps much yet, but to give you an example to think about, I'll use a problem that comes up often when talking about census records -- if you record them as an event, do you record them as a Census event or a Residence? When users attach a census record in Ancestry's online tree system, the tree system creates a GEDCOM residence event. I prefer to create an event for the census for each person in the household, and I choose the census event for the following reasons:

- The instructions for what information was recorded in the census varies from decade to decade and from country to country. For example, in the census of England and Wales, the enumerators were asked to record people who were visitors to the household on census night. If this census is not someone's primary residence, putting in a "they were here" date-and-timestamp for the census as a residence is misleading. It is not their residence, and by giving yourself an erroneous impression that they lived there, you could block yourself from further discoveries.

- If one of your goals is to locate all available census records for every person in your research, it's much easier to spot that you've found them all if they are actually in your database as a census event. Entering the census as such allows me to make use of Family Historian plugins that help with running routine queries, GEDCOM checkers, or other research assistants such as GenSmarts, which are designed to look for missing census records.

For Family Historian, there is an add-on program called Ancestral Sources which allows the user to do enter all the people in the household at one time. This is much easier than creating one census event for the head of household and then trying to copy-and-paste it, modifying it for each person. AS creates the Census event (and birth events as needed) for all the people in the household, much like the Form Gramplet in Gramps already mentioned in this answer.

After entering the basic information in AS, Family Historian's Auto-Source Citation feature allows me to easily select the census from the source list, and add other information from the census (such as the information listed in the Clues in Census Records articles) which was not contained in the Ancestral Sources template. The Auto-Source Citation automatically flags each piece of information I enter with the source citation as I do the data entry.

To me, setting up the source first, working from the source, and extracting the information, with Family Historian putting in the source citation as I go, is a lot easier than the person-oriented workflow of putting all the information in first, then attaching the source citation afterwards.

Even if you can't replicate my workflow in Gramps exactly, you'll understand the information in each source better if you learn to examine sources critically and enter the source as a source into Gramps first, before you do the data entry for the information inside.

Previous Qs that touch on the topic of evidence management and source-based genealogy: