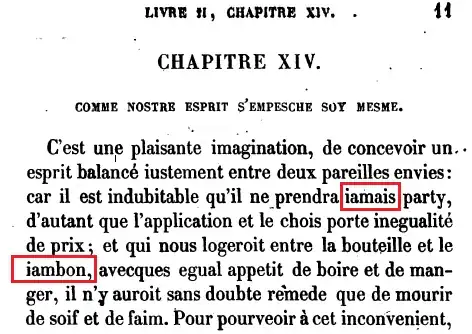

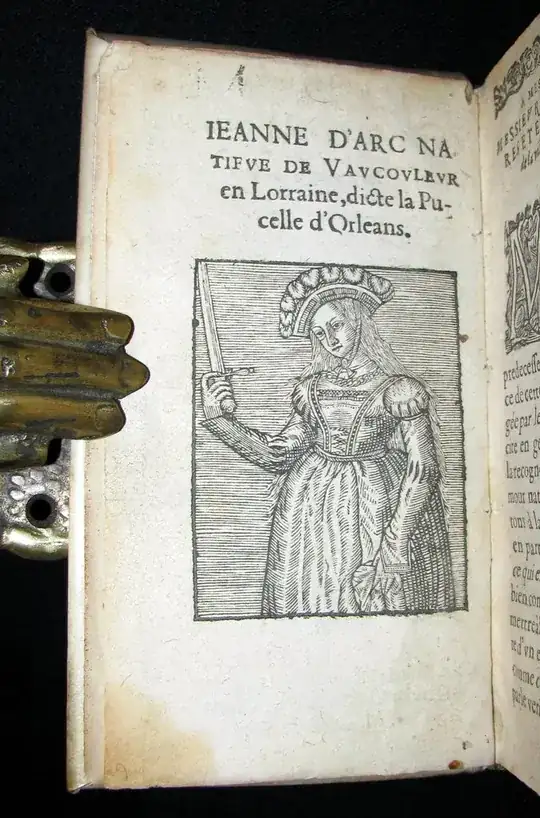

I learned a few days ago that "j" is a fairly new letter. I looked up some samples of antique French books (pre-1633) and found a lot of words like (Saint)"Iaques", "ie", "iamais", "iambon", "iamais", "Ieanne"(d'arc), "iour", "iouer", "iolis".

A Google literal search (word literal in quotes) shows a whole bunch of text that uses "i" where I expect "j" to be. For example:

or

or

I tried to find a text on the evolution of the French language to try to find out when this change occurred and whether it still sounded like /ʒ/ or if there was some kind of dialects using the traditional /j/ pronunciations (like y in "yes") at some point, but I could not find any mention of this change online.

Does anybody know how these words sounded back then, did they still use /ʒ/ or was it /j/? And was it always /ʒ/ or was there a time when French used /j/ or /h/ instead?