Twentieth century grammars and style guides — and a few recent ones — insist that an absolute adjective cannot be compared: something is either perfect, square, or complete or it isn’t. But there is a workaround:

Use the expressions: more nearly perfect, more nearly square, more nearly true, and unique. (Since unique means only one of its kind, it is clear that one does not say more nearly unique.) — Sophie C. Hadida, Pitfalls in English and How to Avoid Them, 1927, 127.

And use them they did:

We, therefore, in order to achieve a more nearly perfect industrial cooperation, in order to give more nearly perfect protection to the human beings engaged in the business of production, and in order to render to the general public a more nearly perfect service, do associate ourselves together and enact the following constitution. — Constitution of the American Guild of the Printing Industry, 1922.

This increase may reflect more nearly complete registration of nonwhite births and also more nearly complete and accurate recording of birth weight for nonwhite infants. Tennessee Vital Statistics, 1961, 9.

The more nearly square the house, the less wall area there is in proportion to the floor area. — Hajime Ota, Houses and Equipment for Laying Hens, 1967, 16.

Some writing guides are still recommending this construction with absolute adjectives:

Some examples are immaculate, perfect, square, round, complete, excellent, and unique. When you use those words in sentences, use them alone or precede them with the terms more nearly or most nearly. For example: Irene's suggestion is the most nearly perfect one of all of them. Your yard is more nearly square than mine. — Thomas L. Means, English and Communication for Colleges, 2006.

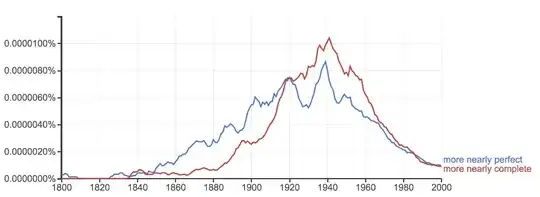

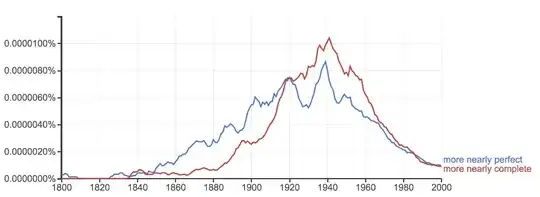

But, as a Google Books query shows, such advice is bucking a trend:

Almost flatlined until 1840 — which is why the US Constitution is happy with “a more perfect Union” but not the printers’ guild — this usage peaks around 1940 with a steep decline thereafter.

There are still contexts, however, where such logical precision is not out of place:

If we take a shorter time than a second this will be more nearly true, approaching the limit of complete truth as the period of time is indefinitely diminished. — Bertrand Russell, Human Knowledge, Its Scope and Limits, 1948, 200.

Insofar as a statement approaches perfection, insofar as the system approaches completeness, our statements become more nearly true. A statement will be more nearly complete to the extent that its opposite is inconceivable. — Frank Northen Magill, Masterpieces of World Philosophy in Summary Form, 1961.

What is nearly true when the unit is small and more and more nearly true as the unit grows smaller is said to be “true in the limit, as the unit decreases.” — Philip Henry Wicksteed, The Alphabet of Economic Science, 1955, 42.

Now these rules always have had more formal written English in mind, which makes Means’ examples so curious. Imagine Irene’s reaction to her most nearly perfect idea or the neighbor at his more nearly square yard. Even at the peak of this construction, I can’t imagine someone commenting on how a lime is more nearly round than a lemon. At least the grammar guides don’t insist on “more nearly spherical.”