It is mentioned in the Encyclopedia of Prostitution and Sex Work Vol 2 ISBN 0-313-32970-2 Pub 2006 Greenwood Press

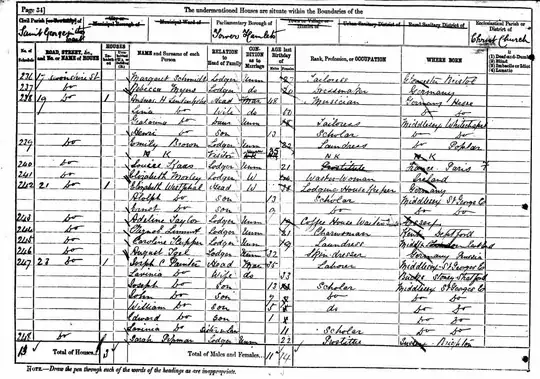

SEAMSTRESSES. "Seamstress" was a euphemism for "prostitute" in census records and other documents of the 19th century in the United States. Historical documentation showing several "seamstresses" sharing common living quarters may generally be assumed to represent a brothel. Whether this occupation was reported by prostitutes or supplied by census enumerators and other officials remains speculative, although potential reasons for both are easily understood.

Legitimate uses of the term should not be confused with the codified use. Other historical and modern euphemisms exist, including laundressess and actressess.

New Essays on Poe's Major Tales by Kenneth Silverman, Cambridge University Press 1993 also states:

Terms like "shopgirl" and "seamstress" were mid-century euphemisms for

women whose chief source of income was their bodies.

This website also discusses the issue with reference to an older work by Charles Horne

In John Cleland's Fanny Hill Mrs Cole's establishment poses as a

"millinery shop". A milliner's or mantua-maker's establishment was

often likened to a house of prostitution, probably an accurate public

perception.

A good many of the fallen women whose bastard children were put into

the Foundling Hospital were seamstresses. Millinery and dressmaking

were a kind of introduction to the prostitute's trade. What trial

records show is that when prostitutes were brought into court (usually

for stealing a gentleman's watch while his trousers were down), they

would describe themselves as apprentices to a mantua-maker, or as

being at one time a mantua-marker before they were led astray. A

character witness for a prostitute will commonly be a mantua-maker,

but I think many judges and juries realized that this mantua-maker

acted as the "aunt" at the head of a small-time ring of streetwalkers.

The professional mantua-maker often took in lodgers to supplement her

income, and the real situation, often as not, is that she would have a

few girl "apprentices" who mended stolen clothes and made new clothes

from stolen textiles while they are not otherwise engaged picking up

men in the street and bringing them to their mistress's upstairs

rooms. It was not uncommon for a gentleman to go into a milliner's

shop and have sex with one of the girls then and there. Though

dressmaking could of course involve a high degree of professional

skill, it also provided good cover for both prostitution and fencing

stolen goods. Very large quantities of linen and silk, plus ribbons

and lace etc., were regularly stolen from warehouses, and found their

way to mantua-makers, milliners, and tailors. Tailors and milliners

often acted as pawnbrokers, which to a great extent meant dealing in

stolen goods. They operated on the boundary between the underworld and

the respectable world.

The occupation of millinery or mantua-making was widely regarded as

just a cover for prostitution. Charles Horne in Serious Thoughts on

the Miseries of Seduction and Prostitution (1783) warned parents not

to allow their daughters to become milliners, mantua-makers, or

workers in the various clothes trades because they were "actually

seminaries of prostitution".