Local non-satiation assumption is required to prove the first welfare theorem.

Consider the following pure exchange economy consisting of two consumers - $1$ and $2$, and two Goods - $X$ and $Y$:

- Preferences of $1$ and $2$ are given by the following utility functions: $u_1(x_1, y_1) = 0$ and $u_2(x_2, y_2) = x_2+y_2$

- Endowments of $1$ and $2$ are given by the following: $\omega_1 = (10,0)$ and $\omega_2 = (0,20)$

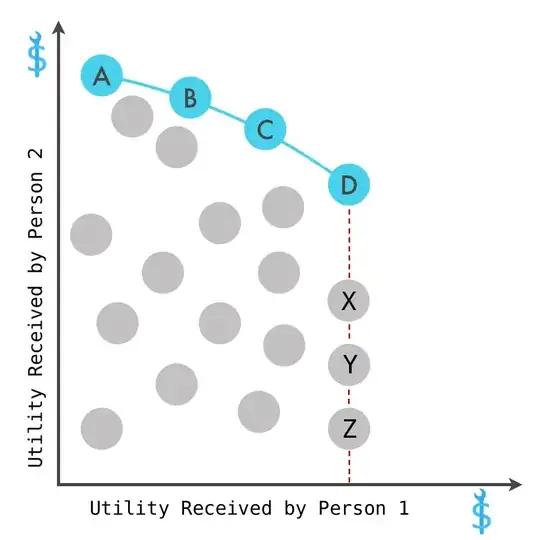

Observe that the endowment allocation is also the competitive equilibrium of this economy i.e. $(x_1^*, y_1^*) = (10, 0)$ and $(x_2^*, y_2^*) = (0, 20)$ supported by any pair of prices $p = (p_X, p_Y)$ satisfying the condition $0 < p_Y \leq p_X$. However, this allocation is not Pareto efficient. This is because an allocation where $2$ consumes all of both the goods is Pareto superior to it.

In this example, it is clear that $1$'s preferences does not satisfy LNS. Also we can see that this condition fails to hold:

$(x_1, y_1) \succsim (x_1^*, y_1^*) = (10,0)$ implies $p_Xx_1+p_Yy_1 \geq p\cdot\omega_1 = 10p_X$

To see this, consider $(x_1, y_1) = (0,0)$.

When preferences satisfy LNS, we can prove that the following proposition is true:

Proposition. If $x_i^*$ is the demand of consumer $i$ when price is $p$ and endowment is $\omega$, then

$x_i\succsim x_i^* \ \Rightarrow \ p\cdot x_i \geq p \cdot \omega_i $.

Proof. Suppose $x_i\succsim x_i^*$ but $p\cdot x_i < p \cdot \omega_i$. Then by LNS, there exists a bundle $x_i'$ sufficiently close to $x_i$, so that $x_i' \succ x_i$ and $p\cdot x_i'<p \cdot \omega_i$ holds. This implies that there exists a bundle $x_i'\succ x_i^*$ which is also affordable, contradicting that $x_i^*$ is the demand.