Treatment effects are causal effects of a binary treatment. Because the treatment is binary, individuals are either treated or they are not treated. For the sake of example assume that the treatment is participation in a money making course - the course is claimed to make you better at making money.

Obviously, the causal effect of such a course could very well be differ from person to person (this is referred to as treatment heterogeneity). Some people may learn a lot from the course and actually improve at making money while others will be bored by the content of the course and experience a zero effect. As usual when important quantitative measures vary across observational units a canonical summary statistic is the average. The Average Treatment Effect (ATE) is simply that: The average of the individual treatment effects of the population under consideration. And the Average Treatment Effect of the Treated (ATT) is simply the average of the individual treatment effects of those treated (hence not the entire population).

To make it formally more clear what the causal effect of treatment is, it is often assumed that for each individual $i$ there exists an amount of money $Y_i^0$ individual $i$ will make without taking the training course. And there also exists an amount of money $Y^1_i$ that individual $i$ will make if she takes course. The causal effect for individual $i$ of participation in the course is then defined as

$$\tau_i := Y_i^1- Y^0_i,$$

the difference in outcome with and without treatment.

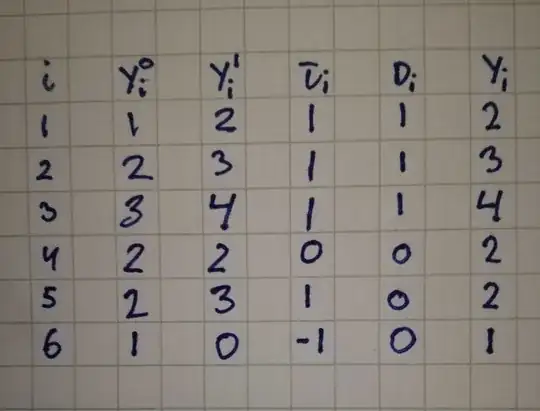

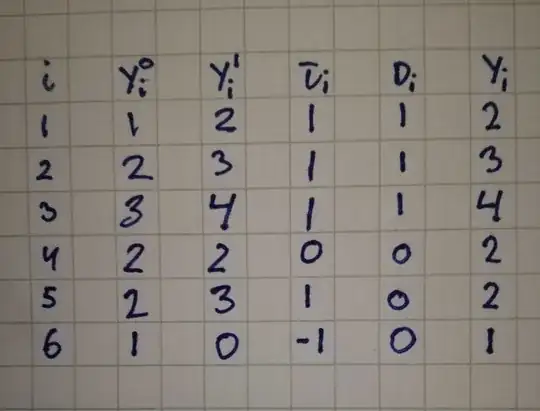

For the sake of example consider the following table for 6 individuals:

It is clear from the table that individual $i=1,2,3$ are treated $D_i=1$ while $i=4,5,6$ are not treated. For those who are treated the observed amount of money made by the individual $Y_i$ is equal to $Y_i^1$. For those not treated the observed amount of money made $Y_i$ is equal to $Y_i^0$. In general this is written as

$$Y_i = D_i Y_i^1 + (1-D_i)Y_i^0.$$

An important part of the setup is therefore that while $Y_i^1$ and $Y_i^0$ are assumed to exist they are not assumed to be observed.

However, getting back to ATT and ATE. In the above example the ATE can be calculated as

$$ATE := \frac{1}{N} \sum_i \tau_i = \frac{1}{N} \sum_i (Y_i^1 - Y_i^0) = \frac{1+1+1+0+1-1}{6} = 0.5,$$

and the average treatment effect of those treated is calculated as

$$ATT := \frac{1}{N_1} \sum_i \tau_i = \frac{1}{N_1} \sum_i (Y_i^1 - Y_i^0) = \frac{1+1+1}{3} = 1.0,$$

where $N_1 = \sum_i D_i = 3$.

In this example ATE and ATT are numerically the same but as you can see they are averages of different sets of individual causal effects. As such they are not necessarily expected to be the same. Try to construct an example yourself where they are different simply by changing the group of treated individuals.

The average treatment effect (ATE) is used when we are interested in the average treatment of the entire population, whereas the average treatment effect of the treated (ATT) is used when we are only interested in the average treatment effect of those treated.