Generalized DID or Staggered DID are DID using staggered treatment events. In Dong,2019's paper, he uses the framework as below:

$Margin_{ikjt}$ = $\alpha$ + $\beta$ $(Leniency Law)_{kt}$ + $\delta$$X_{ikt}$ + $\theta$$_{jt}$ + $\gamma$$_i$ +$\epsilon$$_{ikjt}$ (2)

where $i$, $k$, $j$ , and $t$ index firms, countries, industry, and years respectively. $X_{ikt}$ is a vector of control variables, while $\gamma$ and $\theta$ are firm and year fixed effects. The variable of interest here is $(Leniency Law)_{kt}$.

This is the equation (2) above from section "Effects on cartel detections" of Dong,2019's paper, page893-894. How they assign the samples:

In our estimation, we rely on the staggered nature of the passage of leniency programsto identify their causal effect on firm margins. We follow the standard approach used in theliterature, which relies on the staggered passage of laws in different geographic regions (e.g.,the business combination laws across the United States, as in Bertrand and Mullainathan, 2003).This allows us to compare the change in the margins of firms that were affected by the law to thecontemporaneous change in the margins of the control firms that were headquartered in countries that had not yet passed such a law

This setting is quite similar to the setting in the paper of Dasgupta,2019 as explained thoroughly here. And these two papers using the same sample classification is predictable because they have same author (Alminas Zaldokas)

From staggered DID, as been well-explained by Thomas the variable $(Leniency Law)_{kt}$ is

The binary treatment variable in this more general setting is not the same variable as in the 'classical' difference-in-differences case. Suppose a leniency law is espoused by all firms within treated countries in the year 2000. In this setting you could write this equation more simply as the interaction between a treatment-control dummy and a post-treatment indicator equal to 1 after the law goes into effect in both groups, 0 otherwise. However, once we move away from this setting and the roll out of treatment is staggered or even switching 'on' and 'off' over time, then the "post-treatment" variable is no longer well-defined. To proceed, we must use the 'generalized' difference-in-differences estimator which defines the product term in a different way.

Below is my important critics about the summary statistics of Dong, 2019's paper

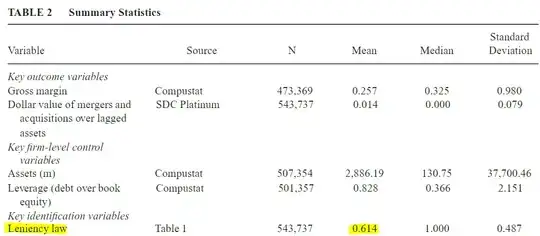

From the description above, the observations of control group should be higher than that of treatment group. Apart from that, in their summary statistic (Table 2, page 889)

It is totally not the case because $(Leniency Law)_{kt}$ only receive the value of 1 when it satisfies both conditions: in the treatment group and during post-treatment period. Therefore, if my logical argument above is correct, there is no way that Leniency law has the mean of 0.614 (more than one half of the concatenating sample of treatment and control group)

Update: Thank to the discussion with @1muflon1, I clarify more about why the observations of control should be higher than that of treatment countries.

For any country, the observations of control sample must be higher than that of the treatment sample. This is because, every country always being treated for 5 years (because this research used the window [-2;+2]; and during the rest period from 1990 to 2012 (excepting the treatment years), this country belongs to control sample based on the setting of generalized DID