A function $v: \mathbb{R}^K_+ \xrightarrow{} \mathbb{R}_+$ is is said to be a valuation function if

- The value of function $v$ at $x = \textbf{0}$ is $0$: $v(\textbf{0}) = 0$

- $v$ is continuous on the domain $\mathbb{R}^K_+$, strictly increasing and strictly concave on $\mathbb{R}^K_{++}$

- For any $p \in \mathbb{R}^K_{++}$, the set $A(p) = \{x \in \mathbb{R}^K_+| v(x) \geq p \cdot x\}$ is compact, the set $A^*(p) = A (p)-\{\bf{0}\}$ is nonempty and lies inside $\mathbb{R}^K_{++}$.

Show that a if $v$ is a valuation function, for every $p \in \mathbb{R}^K_{++}$, for every $x \in \mathbb{R}^K_{++}$, there exist $t>0$ small enough that $$ v(tx) > p\cdot tx $$

In other word, for every $p>\bf{0}$, if you zoom the set $A(p)$ sufficiently close at the origin, it contains all the points near the origin in first quadrant.

Remark 1: This is the problem I reduce from a microeconomics problem I am working on. I want to extend the Inada condition to multivariate case in a topological way. My prototype function is $f(x,y)=x^{\alpha}y^{\beta}$ where $\alpha+\beta <1, \alpha>0,\beta>0$. This family of functions satisfy (1),(2),(3) and the property I want to prove, say (4). I am trying to show either (1),(2),(3) => (4) or should I include (4) as an additional axiom?

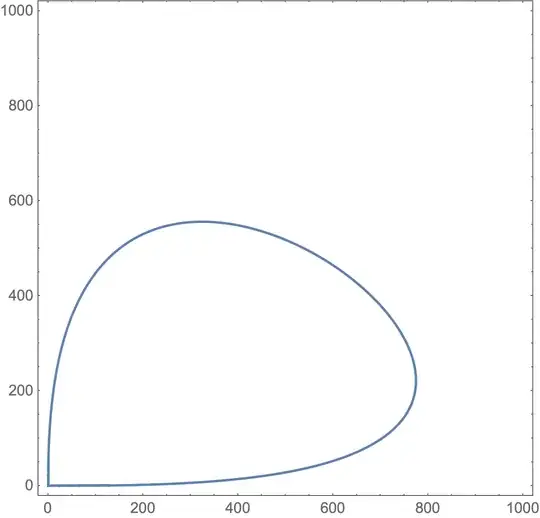

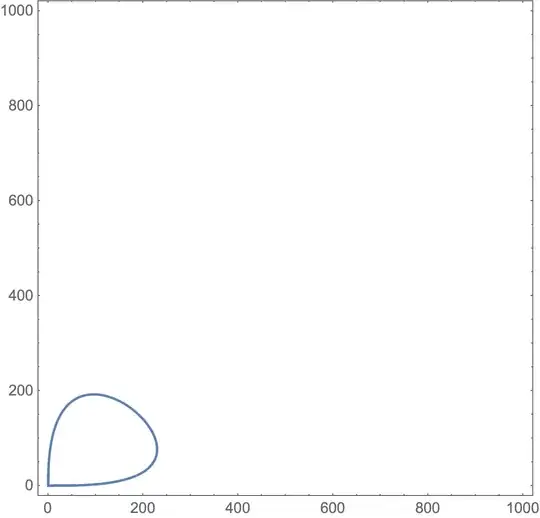

Remark 2: A few examples of $A(p)$

- An example of A(p) when p is small

- An example of A(p) when p is large

(4) is demonstrated by the geometric fact that the contours approach vertical and horizontal axis near $0$.