Kenny LJ's answer is good.

One thing to be aware/ cautious of is that no economy has a single rate of inflation. The rate of inflation for health care in the US is different from the rate of inflation for computer monitors. In an economy with normal inflation, the rates are close enough that you can put together a basket of goods and services that the average person consumes, average together the inflation rates, and come up with a reasonably accurate single rate. Some consumers will experience higher inflation because they spend more on sectors that are experiencing higher rates of inflation and some consumers will experience lower inflation because they spend more on sectors experiencing lower rates of inflation but you'll be reasonably close on average. And it is far, far simpler to talk about "the US rate of inflation" as a single value rather than "the rate of inflation for the average 70 year old in Kansas" vs "the rate of inflation for the average 40 year old in California" even though those two rates are likely different.

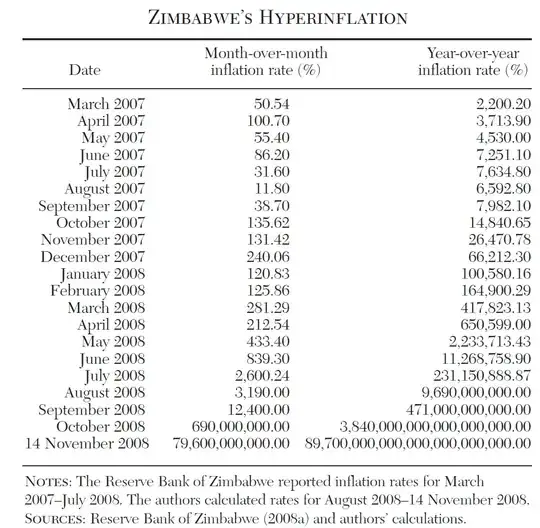

When you have hyperinflation, though, you have several issues. Different sectors still have very different inflation rates but it gets much harder to reasonably average them together because you've got huge differences in different sectors. You're not averaging a 5% rate of inflation for health care with a -2% rate of inflation for computer monitors, you're averaging a 30% percent rate of inflation for wheat due to government subsidies with a million percent rate of inflation for un-subsidized eggs and a 20 million percent rate of inflation for steak. The inflation rate for a store of value that allows you to (relatively) easily get money out of the country (which is what Hanke and Kwok were measuring) could easily be several orders of magnitude larger than the rate of inflation for consumable goods like food. It is plausible that both the IMF measurements and Hanke and Kwok's measurements are decent estimates of inflation rates just for different types of goods. Average consumers focused on buying just enough food to subsist could have been seeing a rate of inflation of 471 billion percent that peaked in September while a handful of wealthy individuals buying stocks in a desperate attempt to get money out of the country and into goods whose value was protected from hyperinflation were experiencing 89.7 sextillion percent inflation a couple of months later.

An additional issue in trying to compute the inflation rate during hyperinflation is simply the sheer rate at which prices would need to change. At an inflation rate of 1 billion percent, prices double every 15.6 days. At an inflation rate of 1 sextillion percent, prices double every 5.7 days. But it often takes time for information about the rate of inflation to move through the economy-- the farmer selling eggs today knows that he needs to get more than he did yesterday but does he need 10% more or 20% more or 50% more? And at the point that you're measuring inflation in billions or trillions of percent, the economy has broken down substantially so you're not going to have a reliable data collector gathering a lot of reliable information on the transactions that are going on. It is entirely possible that observers in town A would see a very different inflation rate than observers in town B in a particular week because A accidentally undershot the average inflation rate in the prior week while B accidentally overshot the average inflation rate. When you have spotty data about a fast-moving trend, that is going to add substantially to the uncertainty of the final result.

The tweets on Sudan and Argentina appear to have the same basic issue. Hanke is measuring the rate of inflation using the black market exchange rate between dollars and the local currency. Most average consumers in those countries are not spending a large fraction of their income buying dollars, they're buying things like food and housing in the local currency. It is entirely possible that those average consumers are experiencing a different rate of inflation than those consumers that are trying to exchange whatever assets they still have into dollars that aren't going to be devalued by crippling inflation.