Why is the length of the apparent solar day less at aphelion than when compared to perihelion.

1 Answers

Why is the length of the apparent solar day less at aphelion than when compared to perihelion?

The TL;DR version:

There's a simple answer to this question, which is that the Earth is orbiting the Sun slower at aphelion than it is at perihelion. A more correct answer (for the current epoch) is that it's a combination of the above effect and seasonal effects. An even more correct answer is that this isn't always the case. There are years far in the future (and far in the past) where the apparent solar day is longer at aphelion than it is at perihelion.

The non-TL;DR version:

It's due to the equation of time, or more precisely, the time derivative of which the equation.

There are two primary factors that result in the length of a solar day differing from a mean solar day over the course of a year. These are the tilt of the Earth's axis with respect to its orbit about the Sun and the eccentricity of the Earth's orbit about the Sun.

If the Earth's axial tilt (obliquity) was zero this question would be easily answered. The solar day is slightly longer than the sidereal day because the Earth needs to rotate a bit more than 360° degrees with respect to the stars to overcome the effects of the Earth's orbital angular velocity. The Earth's orbital angular velocity is slowest at aphelion and fastest at perihelion. This means an Earth with zero axial tilt would see its longest solar day at perihelion and its shortest at aphelion.

Obliquity adds a confounding factor. If the Earth's orbit was circular, the shortest solar days would occur at the equinoxes and the longest at the solstices. The contribution of obliquity to the equation of time is a bit greater than is the contribution due to eccentricity. Since the frequency of the obliquity contribution is twice that of the eccentricity contribution, the obliquity contribution to the length of a solar day is more than twice that of eccentricity.

Currently, perihelion occurs about a couple of weeks after the December solstice while aphelion occurs about a couple of weeks after the June solstice. This means that the effects due to eccentricity and due to obliquity are nearly in phase between the December solstice and perihelion but are nearly out of phase between the June solstice and aphelion.

That the two effects are both positive and nearly in phase between the December solstice and perihelion makes the longest solar day of the year occur between that solstice and perihelion. That the two effects are nearly out of phase June solstice and aphelion makes the solar day at aphelion slightly longer than average, but less than at perihelion.

What about the shortest solar days of the year? These occur near the equinoxes, with the minimum near the September equinox slightly beating out the minimum near the March equinox.

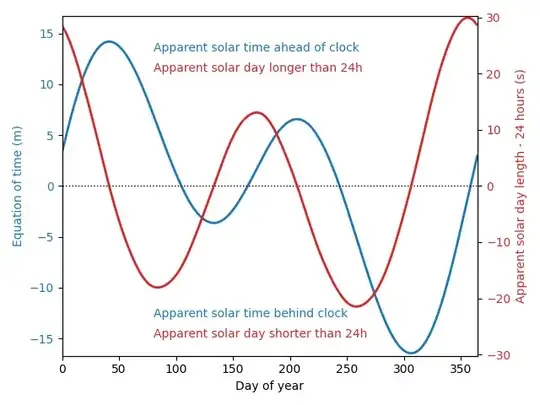

The plot below shows the equation of time (apparent solar time minus wall clock time) in blue and the length of an apparent solar day (time between one solar noon and the next) in red for the year 2022. I've subtracted 24 hours from the length of an apparent solar day for ease of plotting. Both curves show effects from eccentricity and axial tilt, with the blue curve (the equation of time) showing a greater effect from eccentricity than does the red curve.

The python3 script used to generate the above plot is

import ephem

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

obs = ephem.Observer()

obs.lat, obs.lon = '0.0', '0.0'

obs.date = "2021/12/31 06:00"

obs.date = obs.next_transit(ephem.Sun())

prev_transit = obs.date

prev_dtup = prev_transit.tuple()

prev_doy = -1 + (prev_dtup[3] + (prev_dtup[4] + prev_dtup[5]/60.0)/60.0)/24.0

dates = []

lods = []

lod_doys = []

eots = []

eot_doys = []

for i in range(365) :

next_transit = obs.next_transit(ephem.Sun())

lod = (next_transit-prev_transit-1)86400

dtup = next_transit.tuple()

next_doy = i + (dtup[3] + (dtup[4] + dtup[5]/60.0)/60.0)/24.0

eot = (dtup[3]-12)60 + dtup[4] + dtup[5]/60.0

dates.append(next_transit)

lods.append(lod)

lod_doys.append(0.5*(prev_doy+next_doy))

eots.append(eot)

eot_doys.append(next_doy)

obs.date = next_transit

prev_transit = next_transit

prev_doy = next_doy

red = 'tab:red'

blue = 'tab:blue'

black = 'k'

fig, eot_plot = plt.subplots()

lod_plot = eot_plot.twinx()

eot_plot.set_xlabel('Day of year')

eot_plot.set_xlim([0,365])

lod_plot.plot([0,365],[0.0, 0.0], color=black, ls="dotted", lw=1)

lod_plot.text(80, 24.0, "Apparent solar time ahead of clock", color=blue)

lod_plot.text(80, 20.4, "Apparent solar day longer than 24h",color=red)

lod_plot.text(80, -23.4, "Apparent solar time behind clock", color=blue)

lod_plot.text(80, -27.0, "Apparent solar day shorter than 24h",color=red)

lod_plot.set_ylabel('Apparent solar day length - 24 hours (s)', color=red)

lod_plot.plot(lod_doys, lods, color=red, lw=2)

lod_plot.tick_params(axis='y', labelcolor=red)

lod_plot.set_ylim([-30.24,30.24])

eot_plot.set_ylabel('Equation of time (m)', color=blue)

eot_plot.plot(eot_doys, eots, color=blue, lw=2)

eot_plot.tick_params(axis='y', labelcolor=blue)

eot_plot.set_ylim([-16.7,16.7])

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

A sundial will be ahead of a wall clock when the equation of time is positive, behind when the equation of time is negative. In a similar vein, the equation of time increases when the red curve is positive (the length of a solar day is greater than 24 hours) and decreases when the red curve is negative. The extrema in the blue curve (equation of time) corresponds to the zero crossings in the red curve (apparent solar day minus 24 hours). This is because the red curve is essentially a scaled version of the time derivative of the blue curve.

What about the extrema in the red curve? These correspond closely to the equinoxes (local minima) and solstices (local maxima). The extrema in 2022 are at

- 2022/03/25 19:02:04 value = -18.078795180186802

- 2022/06/20 21:56:34 value = 13.067898528426383

- 2022/09/16 08:08:48 value = -21.470782163473018

- 2022/12/23 00:49:59 value = 29.950310073944365

The dates and times of the equinoxes and solstices in 2022 are

- 2022/03/20 15:33:21 (Vernal equinox)

- 2022/06/21 09:13:57 (Summer solstice)

- 2022/09/23 01:03:33 (Autumnal equinox)

- 2022/12/21 21:48:00 (Winter solstice)

These coincide within a few days of the extrema in the length of the solar day. The contributions from eccentricity do play a role in the length of a solar day, but it is minor compared to the role played by axial tilt.

One could imagine times in the future where the effects caused by axial tilt and eccentricity are so far out of sync that the dominating effects of axial tilt that already overwhelm the effects due to eccentricity do so to such an extent that a solar day is longer at aphelion than it is at perihelion. If pyephem remains accurate for the next 18000 years (which is dubious), that happens in the year 19432 (and in many years after that). The dates and times of the six points of interest in 19432 are

- 19432/03/02 11:01:32 (March equinox)

- 19432/04/29 06:27:28 (Aphelion)

- 19432/06/02 23:54:23 (June solstice)

- 19432/09/02 10:33:00 (September equinox)

- 19432/10/19 16:39:16 (Perihelion)

- 19432/12/01 13:51:43 (December solstice)

The equation of time / length of solar day graph for 19432 is shown below. The aphelion and perihelion dates (19432/04/29 06:27:28 and 19432/10/19 16:39:16) are marked with vertical lines. The solar day lengths at these points in time are nearly equal, but the solar day is slightly longer at aphelion than at perihelion.

- 23,597

- 1

- 60

- 102

-

Hello. You have very nicely explained but can you define it in terms of layman because I am not able to visualise the same regarding solar day shorter at aphelion and longer at perihelion. Thank you – Sourabh Jain Jan 09 '22 at 02:03

-

I don't know where else on ESSE to put this, it's a neat math problem that leads to how sidereal and solar days are different: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FUHkTs-Ipfg – JeopardyTempest Mar 15 '24 at 09:08