There are fundamental differences in concept between signals and systems. I will explain this through the idea of unit consistency (see for instance). However, for LTI systems, signals and systems become dual through convolution, since the latter is commutative. Two digressions first, due to the mention in

@Dilip Sarwate answer.

- Digression 1: LTI systems can have the same output for different signals

If two different systems provide the same outputs for some input signals, this means they share some properties. But if their outputs are equal for all inputs, then they essentially have the same impulse response, and they are virtually the same systems.

For instance, imagine you have an input sine at frequency $f$. If both systems cut frequency above $f-\epsilon$, both have the same behavior for that signal, but they can be two different low-pass systems, more signals are needed to distinguish them.

- Digression 2: two different input signals can have the same output through a given LTI system

For instance, a constant signal equal to one, or a 2-periodic signal with {$2,0$} values produce the same output for $2n$-averaging filers.

Back to your question. A system $\mathcal{S}$ turns inputs $X$ into outputs $Y$, respectively with physical units $u_X$ and $u_Y$. So a system can be seen as a unit converter, formally with inner unit $u_Y/u_X$. Generally, the system is "fixed", while inputs my vary. So, there is no reason why $\mathcal{S}$ and $X$ should play the same role.

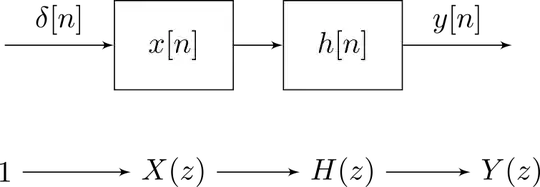

However, when one considers LTI systems, suddenly system properties can be somehow transfered to signals, and vice-versa (as long as the convolution is well-defined). This is related to the fact that convolution commutes with shifts. For simplicity, imagine a "three-tap" system, with $z$-transform response $h_{l}z^{-l}+h_{m}z^{-m}+h_{n}z^{-n}$.

You can directly convert this into a three-band filter bank, with a single input and respective answers $h_{l}z^{-l}$, $h_{m}z^{-m}$ and $h_{n}z^{-n}$. Each branch only provides, for each input, a scale factor and a delay.

But the same happens to signals: each input $x=\{\ldots,x_{l},\ldots,x_{m},\ldots,x_{n},\ldots\}$ can be split into scalar components:

$$x=\ldots+x_{l}\delta_{l}+\ldots+x_{m}\delta_{m}+x_{n}\delta_{n}+\ldots$$

where $\delta_{\cdot}$ denotes the Kronecker symbol. Due to linearity, each component could be fed through the linear system. When everything (signal and system) is split this way, computations are just a bunch of $x_{k}\delta_{k}$

going through a couple of $h_{i}z^{-i}$, which fundamentally are the same operations: a factor/an amplitude and a delayed sample/a delay operator. In other words, $x_{k}\delta_{k}$ going through $h_{i}z^{-i}$ yields the same result as $h_{k}\delta_{k}$ going through $x_{i}z^{-i}$, because the product $h_{k}x_{i}$ is commutative (and preserves unit consistency), and delays commute as well.

In other words, an LTI just yields a weighted sum with weights $h$ on input samples of $x$: $\sum h_i x_{k-i}$, which can be read as well as a weighed sum with weights $x$ on input samples of $h$: $\sum x_i h_{k-i}$. For unit consistency though, one should switch the units of $x$ and $h$.

This interchangeability between signals and systems in the LTI seems to be at play (at first glance) in the polyphase/modulation expression of filter banks, or in matched filtering.