I think Guibas and Stolfi's “edge algebra” formalism is a bit unnecessary.

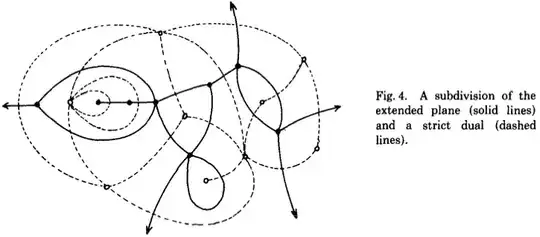

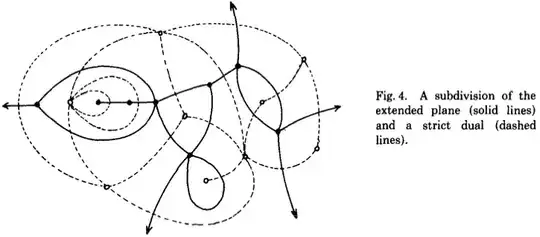

All that's really necessary is to remember the distinction between primal and dual graphs. Each face $f$ of the primal graph has a corresponding dual vertex $f^*$; each edge $e$ of the primal graph has a corresponding dual edge $e^*$; and each vertex $v$ of the primal graph has a corresponding dual face $v^*$. Primal edges connect primal vertices and separate primal faces; dual edges connect dual vertices and separate dual faces. The dual of the dual of anything is the original thing. See Figure 4 in Guibas and Stolfi's paper:

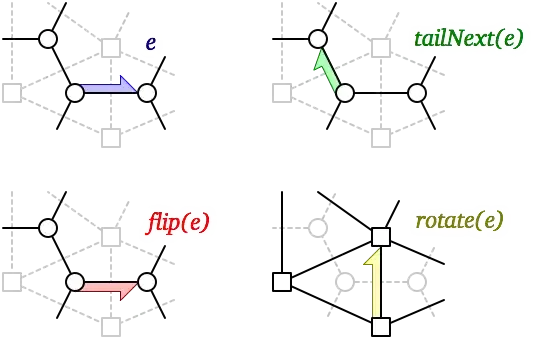

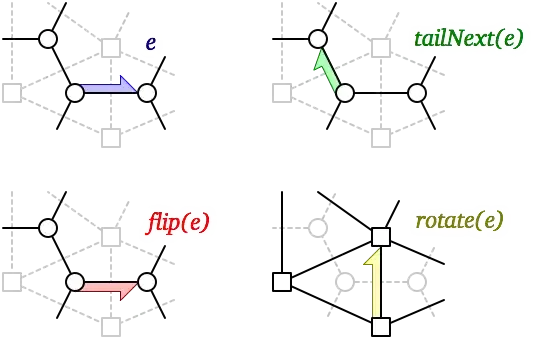

Guibas and Stolfi propose thinking about each edge (either primal or dual) as a collection of four directed, oriented edges; for simplicity, I'll call these darts. Each dart $\vec{e}$ points from one endpoint $\text{tail}(\vec{e})$ to the other endpoint $\text{head}(\vec{e})$, and locally separates two faces $\text{left}(\vec{e})$ and $\text{right}(\vec{e})$. The choice of which endpoint to call $\text{tail}(\vec{e})$ is the dart's direction, and the choice of which face to call $\text{left}(\vec{e})$ is its orientation. (Guibas and Stolfi use “Org” and “Dest” instead of “tail” and “head”, but I prefer the shorter labels, because Unnecessary Abbreviations Are Evil.)

For any dart $\vec{e}$, Guibas and Stolfi associate three related darts:

- $\text{tailNext}(\vec{e})$: The dart leaving $\text{tail}(\vec{e})$ next in counterclockwise order after $\vec{e}$.

- $\text{flip}(\vec{e})$: The “same” dart as $\vec{e}$, but with $\text{left}(\vec{e})$ and $\text{right}(\vec{e})$ swapped.

- $\text{rotate}(\vec{e})$: The dual dart obtained by giving $\vec{e}$ a quarter turn counterclockwise around its midpoint.

These three functions satisfy all sorts of wonderful identities, like the following:

- $\text{right}(\text{tailNext}(\vec{e})) = \text{left}(\vec{e})$

- $\text{right}(\text{flip}(\vec{e})) = \text{left}(\vec{e})$

- $\text{right}(\text{rotate}(\vec{e})) = \text{head}(\vec{e})^*$

- $\text{flip}(\text{flip}(\vec{e})) = \vec{e}$

- $\text{rotate}(\text{rotate}(\text{rotate}(\text{rotate}(\vec{e})))) = \vec{e}$

- $\text{tailNext}(\text{rotate}(\text{tailNext}(\text{rotate}(\vec{e})))) = \vec{e}$

For a complete list, see page 83 of the paper (but beware that the authors use postfix notation $e~Flip$, presumably because it's closer to the declarative code e.Flip). Guibas and Stolfi call any triple of functions satisfying all these identities an edge algebra.

Moreover, given these three functions, one can define several other useful functions like

- $\text{reverse}(\vec{e}) = \text{rotate}(\text{flip}(\text{rotate}(\vec{e})))$ — swap head and tail vertices

- $\text{leftNext}(\vec{e}) = \text{rotate}(\text{tailNext}(\text{rotate}(\text{rotate}(\text{rotate}(\vec{e})))))$ — the next dart after $\vec{e}$ in counterclockwise order around the face $\text{left}(\vec{e})$

Finally, knowing these functions tell you absolutely everything about the topology of the subdivision, and any polygonal subdivision of any surface (orientable or not) can be encoded using these three functions.

The quad-edge data structure is a particularly convenient representation of a surface graph that provides access to all these functions, along with several other constant-time operations like inserting, deleting, contracting, expanding, and flipping edges; splitting or merging vertices or faces; and adding or deleting handles or cross-caps.

Have fun!

*"An edge algebra is an Abstract Algebra (E, E*, Onext, Rot, Flip) satisfying properties E1-E5 and F1-F5"*

– bigmonachus Feb 06 '11 at 19:01