This is not a complete answer by any means, but just a quick estimate on $\mathbb{E}[\sum_{i=1}^k X_{[i]}]$ that is slightly better than the trivial bound of $O(k\sqrt{\log n})$. If this is your goal, I would think it is easier to go directly for it than consider any given $X_{[k]}$. Let $X_S=\sum_{i\in S} X_i$ for a subset $S\subseteq [n]$ and $Y_k=\sum_{i=1}^k X_{[i]}$. Using the same technique as in the first link,

\begin{align}

\exp(t\mathbb{E}[Y_k])&\leq \mathbb{E}[\exp(tY_k)]\\

&=\mathbb{E}\bigg[\max_{S\subseteq [n]:\vert S\vert=k}\exp(tX_S)\bigg]\\

&\leq \sum_{S\subseteq [n]:\vert S\vert=k}\mathbb{E}[\exp(tX_S)]\\

&=\sum_{S\subseteq [n]:\vert S\vert=k}\exp\bigg(\frac{kt^2}{2}\bigg)\\

&={n \choose k}\exp\bigg(\frac{kt^2}{2}\bigg).

\end{align}

Taking (natural) logarithms, we find

$$

\mathbb{E}[Y_k]\leq \frac{\log{n \choose k}}{t}+\frac{kt}{2}.

$$

Optimizing gives $t=\sqrt{\frac{2\log{n \choose k}}{k}}$ so we deduce

$$

\mathbb{E}[Y_k]\leq \sqrt{2k\log{n \choose k}}.

$$

For $k=o(n)$, it is known that $\log{n \choose k}=(1+o(1))k\log(n/k)$, so in this regime, we get

$$

\mathbb{E}[Y_k]\leq k\sqrt{2(1+o(1))\log(n/k)},

$$

which for $k=\log n$, say, is a bit better than the naive bound.

When $k=\alpha n$ for some constant $\alpha$, one instead has $\log{n \choose k}=(1+o(1))H(\alpha)n$, where $H(p)=-p\log p-(1-p)\log(1-p)$ is the entropy function. So in this regime, that would give

$$

\mathbb{E}[Y_k]\leq n\sqrt{2(1+o(1))\alpha H(\alpha)}.

$$

Lower bounds added for completeness: for linear $k$, one can get decent linear lower bounds that degrade as $\alpha\to 0$ but is tight at $\alpha=1/2$. Let $\alpha<1/2$, then by the Chernoff bound,

$$

\Pr(X_{\alpha n+1}\leq 0)\leq \exp\bigg(\frac{-(1/2-\alpha)^2n}{2}\bigg).

$$

It is known that for $i<j$, the conditional distribution of $X_{[i]}$ given $X_{[j]}=x$ is the same as the unconditional distribution of $X_{[i]}$ taken from a sample of size $j-1$ conditioned to be larger than $x$. As we are summing over all $i\leq \alpha n$ and taking expectations, we find that

$$

\mathbb{E}[\sum_{i=1}^{\alpha n} X_{[i]}\vert X_{\alpha n+1}\geq 0]\geq \mathbb{E}[\sum_{i=1}^{\alpha n} Y_i],

$$

where the $Y_i$ are normal random variables conditioned to be larger than $0$, which are known to have expectation $\sqrt{2/\pi}$. We also find that

$$

\mathbb{E}[\sum_{i=1}^{\alpha n} X_{[i]}\vert X_{\alpha n+1}\leq 0]\geq 0,

$$

as for each $x<0$, conditioning on $X_{\alpha n}=x$, by the same reasoning we are now taking expectations over a sample of size $\alpha n$ normal random variables conditioned to be at least $x$, which by symmetry of the normal distribution is at least $0$ (formally, we are using that the sum over the whole sample makes the labelling of the order statistics irrelevant). We conclude that

$$

\mathbb{E}[\sum_{i=1}^{\alpha n} X_{[i]}]\geq \bigg(1-\exp\bigg(\frac{-(1/2-\alpha)^2n}{2}\bigg)\bigg)\alpha n\sqrt{2/\pi}=(1-o(1))\alpha n \sqrt{2/\pi}.

$$

This holds for all $\alpha<1/2$, and by monotonicity of the left hand side in $\alpha$ for $\alpha<1/2$ and taking limits, we can further conclude using the upper bound in the comments

$$

\mathbb{E}[\sum_{i=1}^{n/2} X_{[i]}]=(1-o(1))n\sqrt{1/(2\pi)}.

$$

Obviously similar lower bounds hold for $k=o(n)$ but these aren't super useful as they are of vastly different order than the upper bound.

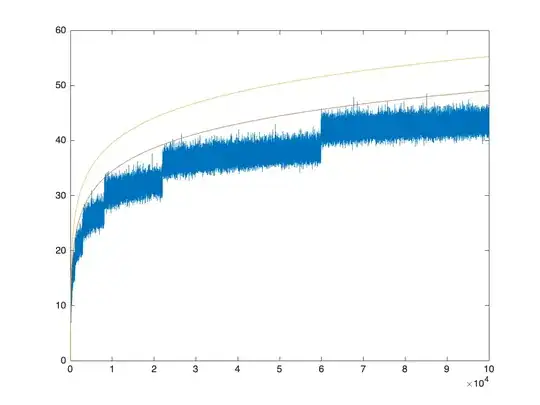

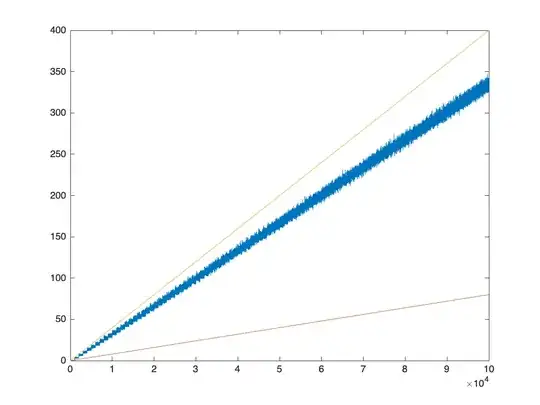

Numerical Simulations: Numerical simulations suggest that these bounds are surprisingly decent in the two regimes mentioned in the post. Note that for any $k$, the function $f(x_1,\ldots,x_n)=\sum_{i=1}^k x_{[i]}$ is Lipschitz, so by Gaussian concentration, one expects simulations to roughly approximate the expectation. For instance, for $k=\log(n)$, here is a plot of the upper bound with that of simulation, with the top curve being the naive bound of $\sqrt{2}\log(n)^{3/2}$ and the lower curve the given bound:

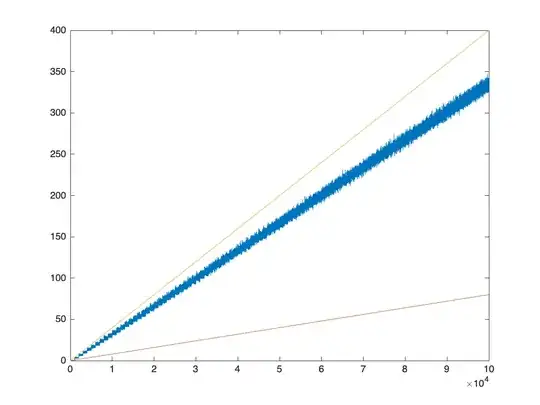

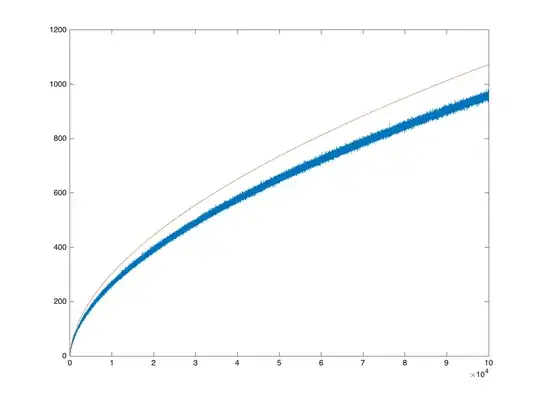

In the linear $k$ regime, for the few values I tried, the constant of the upper bounds seems to be off by a factor of at most $3$ (at $\alpha=1/2$, where we have computed the exact asymptotics). For instance, for $k=n/4$, the plot with the bound looks like:

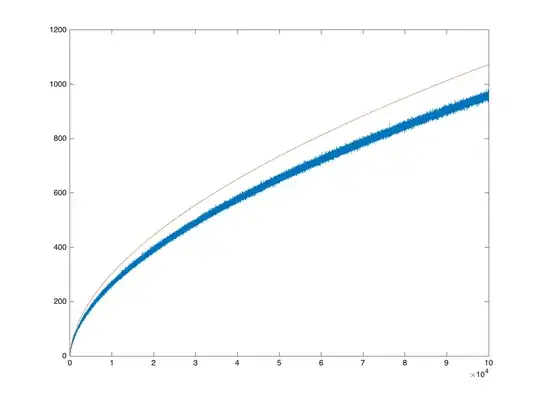

The upper bounds seem pretty good for small constant $\alpha$, while the lower bounds degrade. For instance, here is $\alpha=.001$:

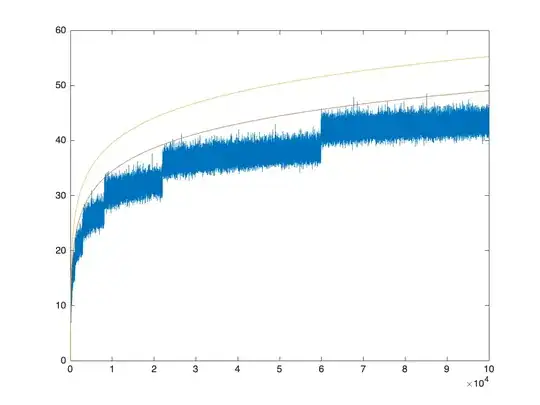

Here's one more plot (because I can't resist) with $k=\sqrt{n}$:  Hope this helps!

Hope this helps!