Here's some empirical data for question 2, based on D.W.'s idea applied to bitonic sort. For $n$ variables, choose $j - i = 2^k$ with probability proportional to $\lg n - k$, then select $i$ uniformly at random to get a comparator $(i,j)$. This matches the distribution of comparators in bitonic sort if $n$ is a power of 2, and approximates it otherwise.

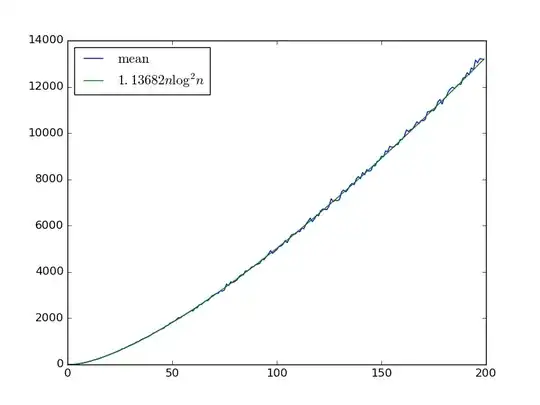

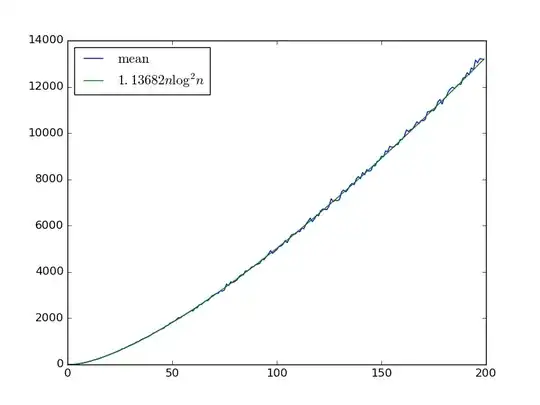

For a given infinite sequence of gates pulled from this distribution, we can approximate the number of gates required to get a sorting network by sorting many random bit sequences. Here's that estimate for $n < 200$ taking the mean over $100$ gate sequences with $6400$ bit sequences used to approximate the count:

It appears to match $\Theta(n \log^2 n)$, the same complexity as bitonic sort. If so, we don't eat an extra $\log n$ factor due to the coupon collector problem of coming across each gate.

It appears to match $\Theta(n \log^2 n)$, the same complexity as bitonic sort. If so, we don't eat an extra $\log n$ factor due to the coupon collector problem of coming across each gate.

To emphasize: I'm using only $6400$ bit sequences to approximate the expected number of gates, not $2^n$. The mean required gates does rise with that number: for $n = 199$ if I use $6400$, $64000$, and $

640000$ sequences the estimates are $14270 \pm 1069$, $14353 \pm 1013$, and $14539 \pm 965$. Thus, it's possible getting the last few sequences increases the asymptotic complexity, though intuitively it feels unlikely.

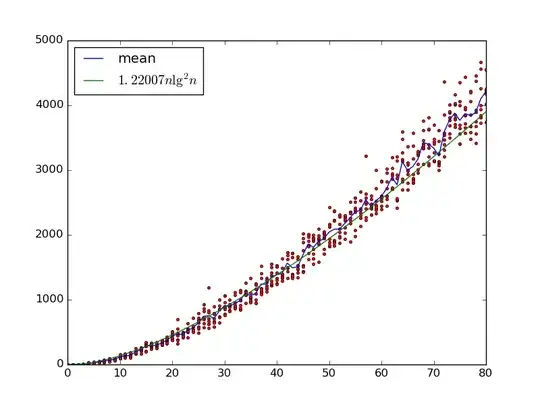

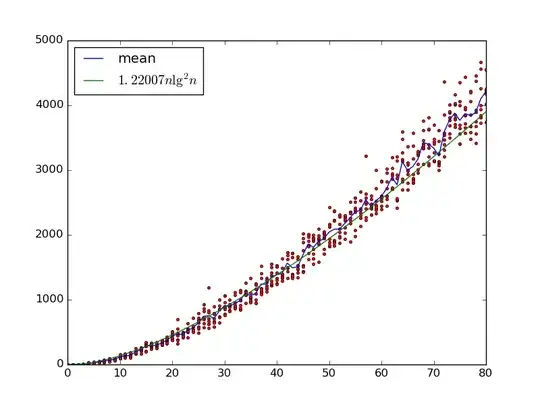

Edit: Here's a similar plot up to $n = 80$, but using the exact number of gates (computed via a combination of sampling and Z3). I've switched from power of two $d = j-i$ to arbitrary $d \in [1,\frac{n}{2}]$ with probability proportional to $\frac{\log n - \log d}{d}$. $\Theta(n \log^2 n)$ still looks plausible.

We can assume all elements are unique and can be mapped to 1...n because if they aren't then the problem is strictly easier. But do you have any other constraint on the input?

– Phylliida Mar 01 '18 at 23:40Then show inductively: if $y$ is the result of comparison sequence $s$ on input $x$, and $y'$ is the result of super-sequence $s'$ of $s$ on $x$, then $y' \preceq y$. So if $y$ is sorted, so is $y'$. – Neal Young Mar 04 '18 at 16:23