EDITS: Added Lemmas 2 and 3.

Here's a partial answer: You can reach position $N$

- in $N$ moves using space $N^{O(\epsilon(N))}$, where $\epsilon(N) = 1/\sqrt{\log N}$. (Lemma 1)

- in $N^{1+\delta}$ moves using space $O(\log N)$ (for any constant $\delta>0$) (Lemma 2).

Also, we sketch a lower bound (Lemma 3): for a certain class of so-called well-behaved solutions, Lemma 1 is tight (up to constant factors in the exponent), and no such solution using poly-log space can reach position $N$ in time $O(N\,\text{polylog}\, N)$.

Lemma 1. For all $n$, it is possible to reach position $n$ in $n$ moves using space $$\exp(O(\sqrt{\log n}))~=~n^{O(1/\sqrt{\log n})}$$

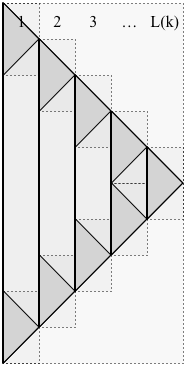

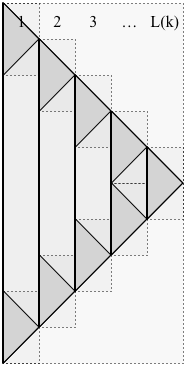

Proof. The scheme is recursive, as shown in the figure below. We use the following notation:

- $k$ is the number of levels in the recursion

- $P(k)$ is the solution formed (with $k$ levels of recursion).

- $N(k)$ is the maximum position reached by $P(k)$ (at time $N(k)$).

- $S(k)$ is the space used by $P(k)$.

- $L(k)$ is the number of layers used by $P(k)$, as illustrated below:

In the picture, time proceeds from top to bottom. The solution $P(k)$ does not stop at time $N(k)$, instead (for use in the recursion) it continues until time $2\,N(k)$, exactly reversing its moves, so as to return to a single pebble at time $2\,N(k)$.

The solid vertical lines partition the $L(k)$ layers of $P(k)$. In the picture, $L(k)$ is five, so $P(k)$ consists of 5 layers. Each of the $L(k)$ layers of $P(k)$ (except the rightmost) has two sub-problems, one at the top of the layer and one at the bottom, connected by a solid vertical line (representing a pebble that exists for that duration). In the picture, there are five layers, so there are nine subproblems. Generally, $P(k)$ is composed of $2\,L(k)-1$ subproblems. Each subproblem of $P(k)$ has solution $P(k-1)$.

The crucial observation for bounding the space is that, at any time, only two layers have "active" subproblems. The rest contribute just one pebble each thus we have

- $S(k) \le L(k) + 2\,S(k-1)$, and

- $N(k) = L(k) \cdot N(k-1)$

Now, we choose $L(k)$ to fully determine $P(k)$. I'm not sure if this choice is optimal, but it seems close: take $L(k) = 2^k$. Then the above recurrences give

- $S(k) \le k\cdot 2^k$, and

- $N(k) = 2^{k(k+1)/2}$

So, solving for $n=N(k)$,

we have $k \approx \sqrt {2 \log n}$

and $S(k) \approx \sqrt {2 \log n}\, 2^{\sqrt {2 \log n}} = \exp(O(\sqrt{\log n}))$.

This takes care of all positions $n$ in the set $\{N(k) : k\in\{1,2,\ldots\}\}$. For arbitrary $n$, trim the bottom of the solution $P(k)$ for the smallest $k$ with $N(k)\ge n$. The desired bound holds because $S(k) / S(k-1) = O(1)$. QED

Lemma 2. For any $\delta>0$, for all $n$, it is possible to reach position $n$ in $n^{1+\delta}$ moves using space $O(\delta 2^{1/\delta}\log n).$

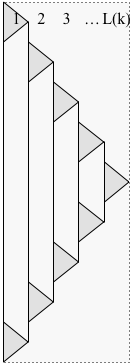

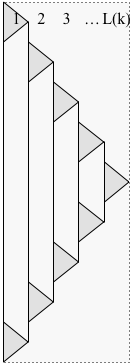

Proof. Modify the construction from the proof of Lemma 1 to delay starting each subproblem until the previous subproblem has finished, as shown below:

Let $T(k)$ denote the time for the modified solution $P(k)$ to finish. Now at each time step, only one layer has a subproblem that contributes more than one pebble, so

- $S(k) \le L(k) + S(k-1)$,

- $N(k) = L(k) \cdot N(k-1)$,

- $T(k) = (2\,L(k)-1)\cdot T(k-1) \le 2\,L(k)\cdot T(k-1) \le 2^k N(k)$.

Choosing $L(k) = 2^{1/\delta}$, we get

- $S(k) \le k 2^{1/\delta}$,

- $N(k) = 2^{k/\delta}$,

- $T(k) \le 2^k N(k)$.

Solving for $S = S(k)$ and $T=T(k)$ in terms of $n=N(k)$, we have $k=\delta \log n$, and

- $S \le \delta 2^{1/\delta} \log n$, and

- $T \le n^{1+\delta}$.

This takes care of all positions $n$ in the set $\{N(k) : k\in\{1,2,\ldots\}\}$. For arbitrary $n$, trim the bottom of the solution $P(k)$ for the smallest $k$ with $N(k)\ge n$. The desired bound holds because $S(k) / S(k-1) = O(1)$. QED

The solutions in the proofs of Lemmas 1 and 2 are well-behaved, in that, for sufficiently large $n$, for each solution $P(n)$ that reaches position $n$ there is a position $k\le n/2$ such that only one pebble is ever placed at position $k$, and the solution decomposes into a (well-behaved) solution $P(N-k)$ for positions $k+1,k+2,\ldots,n$ and two (well-behaved) solutions $P(k)$, each for positions $1,2,\ldots,k$, connected by the pebble at position $k$. With an appropriate definition of well-behaved, let $V(n)$ denote the minimum pebble volume (the sum over time of the number of pebbles at each time) for any well-behaved solution. The definition implies that for sufficiently large $n$, for $\delta=1>0$,

$$V(n) \ge \min_{k<n} V(n-k) + \max(n/2, (1+\delta) V(k)).$$

I conjecture that for every sufficiently large $n$ there is a well-behaved solution that minimizes pebble volume. Maybe somebody can prove it? (Or just that some near-optimal solution satisfies the recurrence...)

Recall that $\epsilon(n) = 1/\sqrt{\log n}$.

Lemma 3. For any constant $\delta>0$, the above recurrence implies $V(n) \ge n^{1+\Omega(\epsilon(n))}$.

Before we sketch the proof of the lemma, note that it implies that any well-behaved solution that reaches position $n$ in $t$ steps has to take space at least $n^{1+\Omega(\epsilon(n))}/t$ at some step. This yields corollaries such as:

- Lemma 1 is tight up to constant factors in the exponent (for well-behaved solutions).

- No well-behaved solution can reach position $n$ in $n\,\text{polylog}\, n$ time steps using space $\text{polylog}\, n$. (Using here that $n^{\Omega(\epsilon(n))} = \exp(\Omega(\sqrt{\log n})) \not\subseteq \,\text{polylog}\, n$.)

Proof sketch. We show $2 V(n) \ge f(n)$ where $f(n) = n^{1+c\epsilon(n)}$ for some sufficiently small constant $c.$ We assume WLOG that $n$ is arbitrarily large, because by taking $c>0$ small enough, we can ensure $2 V(n) \ge f(n)$ for any finite set of $n$ (using here that $V(n)\ge n$, say).

The lemma will follow inductively from the recurrence as long as, for all sufficiently large $n$, we have $f(n) \le \min_{k<n} f(n-k) + \max(n, 2 f(k))$, that is, $f(n) - f(n-k) \le \max(n, (1+\delta) f(k))$ for $k<n.$

Since $f$ is convex, we have $f(n) - f(n-k) \le k f'(n)$. So it suffices if $k f'(n) \le \max(n, (1+\delta) f(k)).$

By a short calculation (using $f(n)/n = e^{c\sqrt{\log n}}$ and $f'(n)=(f(n)/n)(1+c/(2\sqrt{\log n})),$ and using a change of variables $x = \sqrt{\log k}$ and $y=\sqrt{\log n}$), this inequality is equivalent to the following:

for all sufficiently large $y$ and $x\le y$, $e^{cy}(1+c/(2y)) \le \max(e^{y^2 - x^2}, (1+\delta) e^{cx})$. Since $1+z\le e^z$, and $e^z\le 1+2z$ for $z\le 1$, it suffices to show

$e^{cy + c/(2y)} \le \max(e^{y^2 - x^2}, e^{2\delta+cx}),$ that is,

$$cy + c/(2y) \le \max(y^2 - x^2, 2\delta+cx).$$

If $y \le x + 0.1\delta/c$, then $cy+c/(2y) \le cx + 0.2\delta$ (for large $y$) and we are done, so assume $y\ge x + 0.1\delta/c$. Then $y^2-x^2 \ge 0.1y\delta/c$ (for large $y$), so it suffices to show

$$cy + c/(2y) \le 0.1 y\delta/c.$$

This holds for sufficiently small $c$ and large $y.$ QED