Suppose we have a finite set $L$ of disks in $\mathbb{R}^2$, and we wish to compute the smallest disk $D$ for which $\bigcup L\subseteq D$. A standard way to do this is to use the algorithm of Matoušek, Sharir and Welzl [1] to find a basis $B$ of $L$, and let $D=\langle B\rangle$, the smallest disk containing $\bigcup B$. The disk $\langle B\rangle$ may be computed algebraically using the fact that, since $B$ is a basis, each disk in $B$ is tangent to $\langle B\rangle$.

($B\subseteq L$ is a basis of $L$ if $B$ is minimal such that $\langle B\rangle=\langle L\rangle$. A basis has at most three elements; in general for balls in $\mathbb{R}^d$ a basis has at most $d+1$ elements.)

It is a randomised recursive algorithm as follows. (But see below for an iterative version, which may be easier to understand.)

Procedure: $MSW(L, B)$

Input: Finite sets of disks $L$, $B$, where $B$ is a basis (of $B$).

- If $L=\varnothing$, return $B$.

- Otherwise choose $X\in L$ at random.

- Let $B'\leftarrow MSW(L-\{X\}, B)$.

- If $X\subseteq\langle B'\rangle$ then return $B'$.

- Otherwise return $MSW(L, B'')$, where $B''$ is a basis of $B'\cup\{X\}$.

Used as $MSW(L, \varnothing)$ to compute a basis of $L$.

Recently I had cause to implement this algorithm. After verifying that the results were correct in millions of randomly-generated test cases, I noticed that I had made an error in the implementation. In the last step I was returning $MSW(L-\{X\}, B'')$ rather than $MSW(L, B'')$.

Despite this error, the algorithm was giving the right answers.

My question: Why does this incorrect version of the algorithm apparently give correct answers here? Does it always (provably) work? If so, is that also true in higher dimensions?

Added: some misconceptions

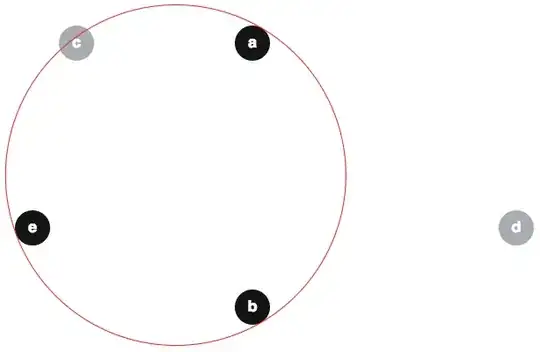

Several people have proposed incorrect arguments to the effect that the modified algorithm is trivially correct, so it may be useful to forestall some misconceptions here. One popular false belief seems to be that $B\subseteq\langle MSW(L, B)\rangle$. Here is a counterexample to that claim. Given disks $a,b,c,d,e$ as below (the boundary of $\langle a,b,e\rangle$ is also shown in red):

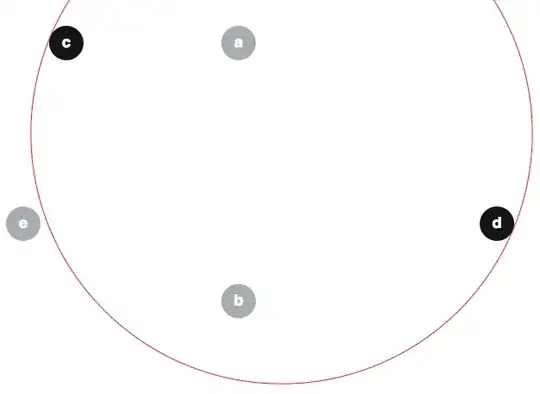

we can have $MSW(\{c, d\}, \{a,b,e\})=\{c,d\}$; and note that $e\notin\langle c,d\rangle$:

Here is how it can happen. The first observation is that $MSW(\{c\},\{a,b,e\})=\{b,c\}$:

- We wish to compute $MSW(\{c\},\{a,b,e\})$

- Choose $X = c$

- Let $B' = MSW(\varnothing, \{a,b,e\}) = \{a,b,e\}$

- Observe that $X\notin\langle B'\rangle$

- So let $B''$ be a basis of $B'\cup\{X\} = \{a,b,c,e\}$

- Observe that $B''=\{b,c\}$

- Return $MSW(\{c\}, \{b,c\})$, which is $\{b,c\}$

Now consider $MSW(\{c, d\}, \{a,b,e\})$.

- We wish to compute $MSW(\{c, d\}, \{a,b,e\})$

- Choose $X=d$

- Let $B' = MSW(\{c\}, \{a,b,e\}) = \{b,c\}$

- Observe that $X\notin\langle B'\rangle$

- So let $B''$ be a basis of $B'\cup\{X\} = \{b,c,d\}$

- Observe that $B''=\{c,d\}$

- Return $MSW(\{c,d\}, \{c,d\})$, which is $\{c,d\}$

(For the sake of definiteness, let us say that the disks $a,b,c,d,e$ all have radius 2, and are centred at $(30,5)$, $(30,35)$, $(10, 5)$, $(60, 26)$, and $(5, 26)$ respectively.)

Added: an iterative presentation

It may be easier to think about an iterative presentation of the algorithm. I certainly find it easier to visualise its behaviour.

Input: A list $L$ of disks

Output: A basis of $L$

- Let $B\leftarrow\varnothing$.

- Shuffle $L$ randomly.

- For each $X$ in $L$:

- If $X\notin\langle B\rangle$:

- Let $B$ be a basis of $B\cup\{X\}$.

- Go back to step 2.

- Return $B$.

The reason the algorithm terminates, incidentally, is that step 5 always increases the radius of $\langle B\rangle$ – and there are only finitely many possible values of $B$.

The modified version doesn’t have such a simple iterative presentation, as far as I can see. (I tried to give one in the previous edit to this post, but it was wrong – and gave incorrect results.)

Reference

[1] Jiří Matoušek, Micha Sharir, and Emo Welzl. A subexponential bound for linear programming. Algorithmica, 16(4-5):498–516, 1996.