I'm not sure if the question requests particularly beautiful algorithms, but as far as useful and simple algorithms go..

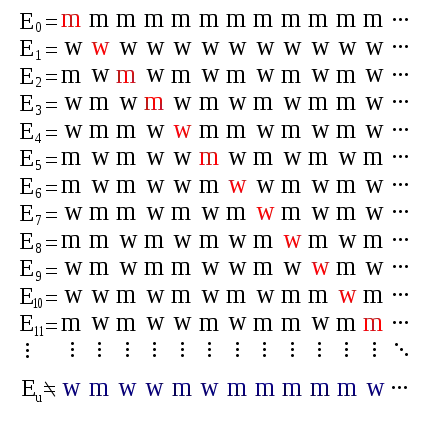

I propose steepest descent. By this I specifically mean an iterative minimization technique for a function $f$ over a domain with norm $\|\cdot\|$ which, at every step, from an iterate $x$, performs linesearch in the direction(*) $v := \textrm{argmin}_u \{\nabla f(x)^T u : \|u\| = 1\}$. (For two texts which use this terminology and provide discussion, see Boyd/Vandenberghe or Hiriart-Urruty/Lemarechal.)

When $\|\cdot\|$ is the $l_2$ norm, this gives gradient descent, which was certainly known to Cauchy but arguably known by every living organism. When $\|\cdot\|$ is the $l_1$ norm, this is greedy coordinate ascent, which includes boosting, which is similar to Gauss-Seidel iterations.

When $\|\cdot\|$ is any norm over $\mathbb{R}^n$ and $f$ is strongly convex, this method exhibits linear convergence (i.e. $\mathcal{O}(\ln(1/\epsilon))$ iterations to error $\epsilon$); for a proof of this, see Boyd/Vandenberghe. (The constants are bad because it uses the ones provided by norm equivalence.)

Certainly, there are methods with faster convergence, the ability to handle nonsmooth objectives, etc. But this method is simple and can work decently, and thus is in widespread use, and always will be.

(*) There may be more than one minimizer (consider $l_1$ norm), but there is always at least one (gradients are linear, and the set is compact).