We have the following theorem:

Let $\Pi$ be a perfectly-secret scheme over message space $M$, and let $K$ be determined by $Gen$. Then $|K| ≥ |M|$.

How can we prove that the above theorem is valid for almost perfect secrecy? The definition for almost perfect secrecy is as follows:

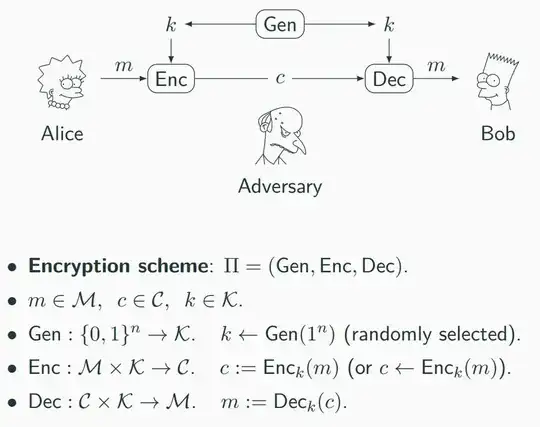

The encryption scheme $\Pi = (Gen,Enc,Dec)$ over a message space $M$ is almost perfectly secret or $\varepsilon$-perfectly secret if for every probability distribution over $M$, $\forall m \in M$ and $\forall c \in C$ for which $Pr[C = c] > 0$ and for a constant $\varepsilon < 1$:

$$|Pr[M = m|C = c] - Pr[M = m]| < \varepsilon$$

EDIT