Neither is it binary, nor is there a formula.

is there a more scientific guideline out there that somehow measures safety objectively

No, there isn't, and there isn't anything that could be objectively measured, much less calculated with a formula.

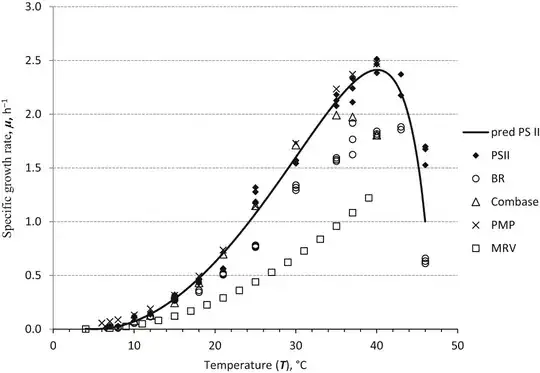

The most relevant thing that can be determined in numbers (and by observation rather than by formula) are bacterial growth rates under well-defined conditions. So, let's say that you know the growth rate of an average strain of E. Coli in medium, dependent on temperature. You look up the rate at 4 C and 4.1 C and ... what? This information is woefully insufficient for anything, certainly not for calculating the number of Salmonella in a piece of meat sitting in your refrigerator when you get it out and eat it. And not even this is the number you'd want - I suppose you were imagining more something like a numerical value for the probability that you get sick. Which is in no way attainable.

And even if you were imagining the "probability that I get sick" number, so what? Safety, in its idealized form, isn't a probability, it's the assertion that the probability of a negative event is lower than an acceptable threshold. Where do you get such a threshold? If you knew, "If my meat was kept at 4 C, my chance of food poisoning is 0.00245%, and if it was kept at 4.1 C, it's 0.00319%", how do you decide which if 0.00319% is still OK? Yes, you could just say "anything under 1% is fine with me", but that would be again an absolutely arbitrary boundary.

And for a regulatory agency, it wouldn't be sufficient to have a formula telling them that "if food is kept at X degrees, the number of people getting sick will be within Y percent point of a predefined threshold". Rather, they'd have to take into account (if they wanted numerical precision) that, once they issue that rule, not everybody will follow it. Fridges set at 4 C vary around 4 C, but don't stay at that temperature all the time. Some even vary around 4.1 C or even 5 C, if their thermostat is really bad. And then people will sometimes just not follow the rules - and whether they follow them will also depend on how they're stated.

For all these reasons, setting the food safety rules is a legal process. The agency takes the available information into account. It will hopefully have scientists create complex predictive models for a few different scenarios. These models will not be "a formula", but huge calculations ran on supercomputers, just like weather forecast models or the covid forecast models you might have encountered during the pandemic. All of them will give different results for the risk, and maybe for other variables like projected healthcare costs, or lost economic utility from missed workdays*. Then there will be all kind of stakeholder wishes and practical problems to consider. Imagine that tomorrow, an updated model projects that the healthcare costs would be 30% less if the rule was changed to 3.8 C. Can you imagine the outcry from the restaurant lobby who'd have to replace all their fridges?

So, what they do is to make a reasonable decision, but not based on precise numbers. The resulting rule doesn't measure safety (as explained above, there isn't any natural number that would be measureable anyway), it defines safety. It's a state act, much like drawing a border defines where France ends and Germany begins, rather than somehow objectively finding out where in nature, France ends and Germany begins. Mostly because safety, especially in the meaning used by food agencies, is a concept from the legal sphere and at best the social sphere, not from the sphere of the natural sciences.

This is not to say that you can't find quantitative information on the risk of food poisoning. There are all kinds of objective information, including numerical information, about bacterial growth, risk and incidence of food poisoning, and so on. What doesn't exist is a way to transform this sea of information into the knowledge of "if I eat meat that was held at 4.1 C instead of 4, I know what will happen differently."

* I'm describing how a government would act nowadays. I don't know if this is what was done historically when the FDA came up with the 4 C, since this kind of mathematical modelling wasn't feasible for most of the 20th century.