Does stellar parallax only occur parallel to the ecliptic, or has it been observed in other directions, too?

-

1very similar question: "Does parallax measurement depend on position in the sky?" – Geremia Nov 21 '22 at 17:54

-

1No discussion here would be complete without pointing you to the GAIA spacecraft - humanity's most amazing parallax machine. – Fattie Nov 23 '22 at 01:48

4 Answers

Parallax motion is seen on the plane of the Earth's orbit projected onto the sky towards the star in question and is not restricted to motion parallel to the ecliptic plane.

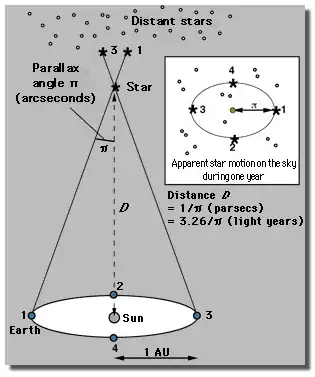

The parallax motion of a star on the sky, with respect to a reference frame defined by extremely distant quasars, is in the form of an ellipse.

If the star lies in the ecliptic plane then the semi-minor axis of the ellipse would be zero and all the parallax motion would be in the direction of the ecliptic plane. This is because from the star's perspective, the Earth's orbit around the Sun looks like a back-and-forth along a straight line.

If the star is near the ecliptic pole, the parallax motion would be almost circular. The diameter of that circle would be similar to the length of the parallax line for a star of similar distance but in the ecliptic plane. That is because from the star's perspective it is looking "top-down" on the Earth's orbit and sees an almost circular orbit.

For stars at intermediate ecliptic latitude, the parallax motion is an ellipse with the semi-major axis along the same direction as the long-axis of the ellipse of the Earth's orbit as seen from the star.

The picture below shows an example of the parallax motion for a star at intermediate ecliptic latitude, as viewed from the Earth. At a guess, judging from the ratio of the semi-major to semi-minor axes of the observed parallax ellipse, I would say the star is meant to be at an ecliptic latitude of around 45 degrees.

The New Horizons spacecraft has flown outside the ecliptic plane and measured parallaxes (for a few stars), where the principal displacement would not be along the ecliptic plane.

- 151,483

- 9

- 359

- 566

-

1I'd argue that in all these cases the apparent movement of the star is parallel to the ecliptic plane. – Paŭlo Ebermann Nov 22 '22 at 00:20

-

1@PaŭloEbermann What about a star offset 45 degrees from the ecliptic? – Jason Goemaat Nov 22 '22 at 04:45

-

1@PaŭloEbermann the only plane of motion is the plane of the sky. An ellipse cannot be in any other plane, except when it's a line (if the star is on the ecliptic equator). – ProfRob Nov 22 '22 at 07:37

Does stellar parallax only occur parallel to the ecliptic ...?

No. For example, Polaris has an observable parallax, and that's because Polaris is a somewhat nearby star (about 99 parsecs or 323 light years away). The stellar parallax is independent of ecliptic latitude and depends only on the distance to the star in question.

Consider a line from the star in question to the Sun. By definition, this line is normal to a plane that passes through the Sun. There are two cases of interest:

- The normal plane is not the ecliptic plane. In this case, the normal plane and ecliptic plane will intersect in a line that passes through the Sun. This line on the ecliptic will be normal to the line from the star to the Sun. This is the line on which parallax is measured.

- The normal plane is the ecliptic plane. In this case, pick any point on the Earth's orbit about the Sun and its antipode to define a line on the ecliptic (and on the normal plane). All such lines will be normal to the to the line from the star to the Sun. Ignoring eccentricity, the observed parallax angle will be the same regardless of the chosen point.

In both cases, the very simple expression $dp = 1$ arises, where $d$ is the distance to the star in parsecs and $p$ is the parallax angle in arc seconds. (This assumes that $\tan(x)=x$ where $x$ is in radians. This is very close to true for very small values of $x$.)

- 33,900

- 3

- 74

- 125

Perhaps a simpler explanation:

Imagine traveling in a straight line down a long road. You will observe parallax of objects in every direction, except objects you're heading directly towards. For all objects you're not traveling directly towards, it doesn't matter if they're up, down, left or right, the same parallax effects are observed in all those directions. Objects in front of you and behind you, but still not directly on your path, will be affected by diminishing parallax based on how far away they are from your line of path.

At some point, imagine taking a 90 degree turn and traveling the same distance. Now you observe parallax on all of the objects you didn't before.

So, since the Earth's orbit is nearly circular, we do get to observe the same parallax effects in every direction, just at different times of the year.

- 5,857

- 1

- 14

- 31

Hold a round coin at arm's length, and close one eye.

No matter how you rotate the coin, the apparent distance between the two furthest points on the edge of the coin will always be the same.

If we imagine the edge of the coin as the (nearly) circular orbit of the Earth and our open eyeball as a near-field star, we realize that parallax magnitude is independent of the observer's orbital orientation.

If we were observing from a planet with a highly elliptical orbit, the direction of the observation could significantly impact the magnitude of the parallax effect, but the Earth's orbit is fairly circular ($e \approx{0.01671}$).

- 16,240

- 4

- 43

- 96