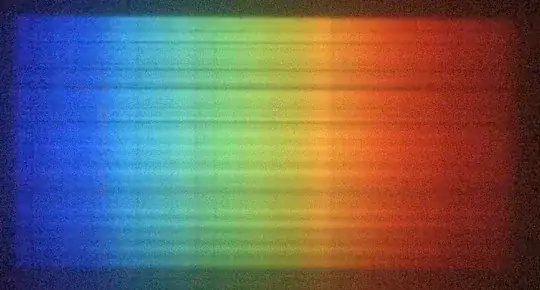

I am an astronomy teacher, and made some kind of spectrograph with a difraction grating, a 3D printed slit, water pipes and a reflex camera. With a group of students we got this picture of the solar spectrum:

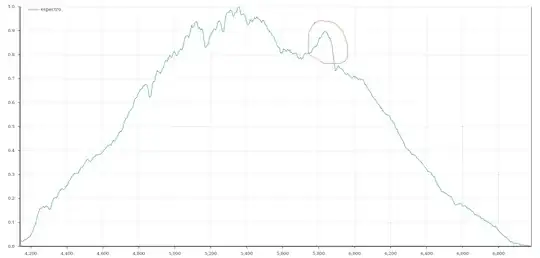

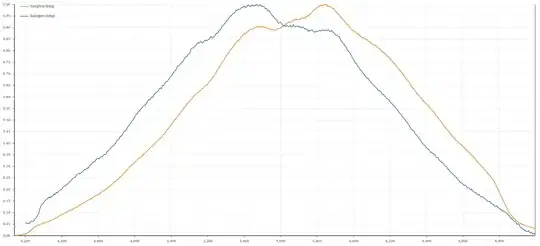

Then we created a luminosity profile with this program to study the position of the absorption lines, and we noticed a strange "bump" in the yellow part of the spectrum (I mark it below with a red curve):

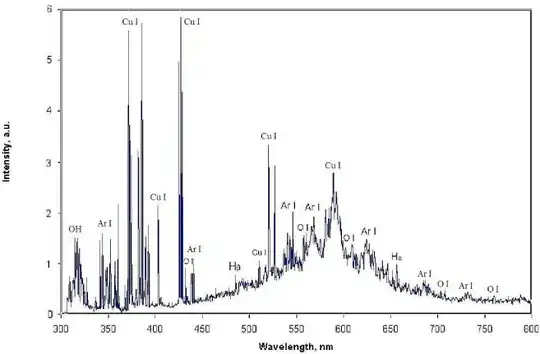

We don't have a clue to what causes it. May be the camera? It's a Canon EOS T5i. We took the picture in RAW mode, and "debayered" it with this program: Fitswork.

Edit:

The diffraction grating is the Star Spectroscope, manufactured by Rainbow Optics. It's of the transmission type and, according to this site, it has 200 lines per milimeter.

Thank you very much in advance!

Edit 2:

As can be seen, the spectrograph is very... DIY. There are no other optical elements: just the slit, the grating, and the camera with it's zoom lens. Also, the grating is iluminated normally.